Black hole thermodynamics

August 31, 2015. An introduction to black hole thermodynamics, based on a talk given to undergraduates at the University of Melbourne.

Table of Contents

1. Intro

One of the most remarkable discoveries of late 20th century physics is that a black hole behaves like a box of hot gas; it has thermodynamic properties like temperature, entropy and energy. But unlike a hot gas, where we have a good microscopic understanding of how these properties arise, we are still trying to figure out the corresponding microscopic physics of the black hole! This is one of the holy grails of theoretical physics. We will focus on the beautiful thermal properties of black holes, and leave the mysteries of quantum gravity for another day.

To start off with, what is a black hole? No doubt you’ve heard about them. Loosely speaking, black holes are regions of spacetime where gravity is so strong that light, and therefore massive particles, can’t escape. There is a better analogy in terms of traffic. One of Einstein’s insights from special relativity was the existence of a universal speed limit: the speed of light $c$, which is the same in all reference frames. Einstein’s general theory of relativity adds gravity into the mix, and allows the direction of light to change locally in interesting ways. But the speed limit remains in place: you can never locally travel faster than light. It is the one traffic rule of the universe!

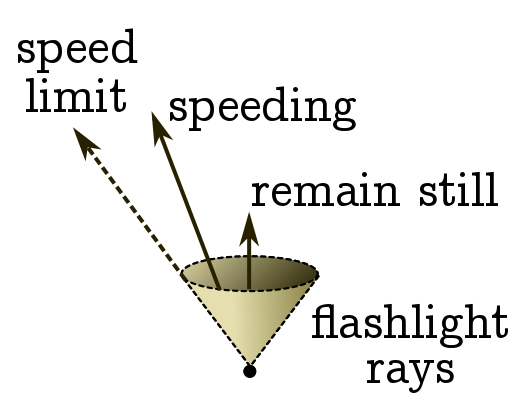

We can visualise this speed limit using light cones, which I hope you remember from your special relativity class. At each point, we imagine shining a flashlight in all directions, and graphing where the light travels. The result is a cone (in two spatial dimensions, and a sort of “hypercone” in higher dimensions). Obeying the speed limit means that you can only move within the cone traced out by the rays from the flashlight. Remaining still corresponds to travelling along the axis of the cone, while speeding means your velocity vector is tilted with respect to the axis; there is a maximum tilt as you hit the edge of the cone, corresponding to travelling at the speed of light.

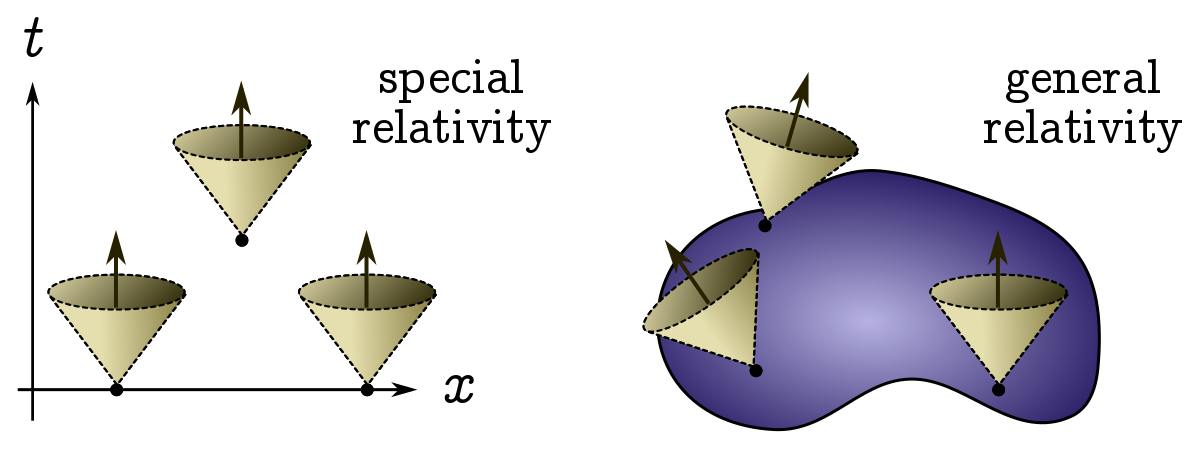

In special relativity, there is a light cone at every point of spacetime, and they all point in the same direction. In order for this to make sense, we need to have coordinates that cover all of spacetime. In your special relativity class, you will have seen that time $t$ and spatial directions $\vec{x}$ do the job.

In general relativity, we are no longer guaranteed to have well-defined global coordinates, which I’ve suggested above by drawing spacetime as a blob rather than a neat Cartesian plane. But there is always a light cone, though its direction can change, and the universal speed limit always applies.

2. Black holes and the area theorem

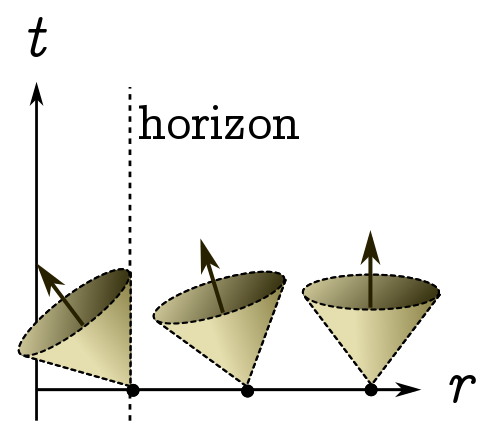

In terms of our traffic analogy, a black hole is a one-way street. The simplest black hole is a spherical one-way street, sitting at the origin. It was discovered by German physicist Karl Schwarzschild, in 1915, while he was serving on the Russian front. We can picture what’s happening by drawing a vertical axis for time $t$ measured outside the black hole, and a horizontal axis for radial distance from the black hole.

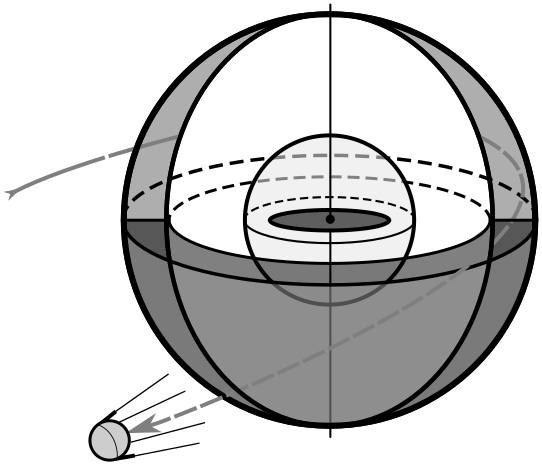

At each point, we can draw a light cone. Far away from the black hole, light cones are upright, and space looks neatly divisible into time $t$ and the radial direction $r$, just like flat space. We therefore think of $t$ and $r$ as the time and radial coordinates of someone very far from the black hole, often called an asymptotic observer. But as we get closer to $r= 0$, the light cones tip over more and more, until eventually, at the dotted line, no part of the light cone points in the negative $r$ direction. Any direction you point your flashlight, the light ends up closer to the black hole! The dotted line is called the Schwarzschild radius, or horizon radius. A consequence of the universal speed limit is that once you cross the Schwarzschild radius, you can never return.

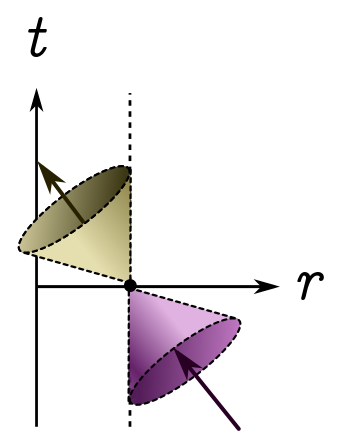

However, note that you can still receive signals. The light cone outlined by your flashlight is called the future light cone, and it tells you where you can send signals (including yourself). The past light cone tells you where you can receive signals from; think of it as a radar, rather than a flashlight. As we can see, from the picture below, even after you fall into the black hole, you can still watch your favourite TV shows beamed from Earth.

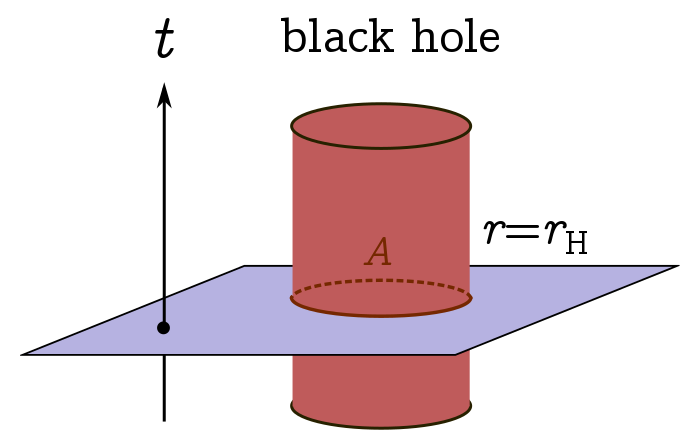

The horizon extends in time as well as space; in two spatial dimensions, for instance, it sweeps out as a tube. To find the area of a black hole at a given time $t$, we intersect the tube with a slice of spacetime at constant $t$, and calculate the area $A$ of that intersection.

Let’s find the area for a spherical black hole in four dimensions (since that’s the universe we live in). By a pedagogically happy fluke, we can use classical reasoning and get the right answer! So, imagine a star of mass $M$ collapses spherically in on itself to form a black hole. At any point in time, from symmetry the horizon will be a sphere. Our dodgy classical assumption is that the horizon radius $r_\text{H}$ is where the escape velocity equals the speed of light $c$; this is the Newtonian analogy to the light cone completely tipping over.

You may remember that the escape velocity is just the velocity needed to escape the Newtonian gravitational field of an object, but with no kinetic energy left over. That’s just enough gas to get to infinity. Mathematically, if $m$ is the mass of a test particle whose velocity approaches $c$, and $r_\text{H}$ the radius of the event horizon, then kinetic plus potential energy at the horizon is

\[K + U = \frac{1}{2}mc^2 - \frac{GMm}{r_\text{H}} = 0 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad r_\text{H} = \frac{2GM}{c^2}.\]This is also called the Schwarzschild radius, and agrees with Schwarzschild’s calculation in general relativity. The area is then

\[A = 4\pi r_\text{H}^2 = \frac{16\pi G^2 M^2}{c^2} \propto M^2.\]Since the area is proportional to mass squared, and things can only go into the black hole, it is plausible that the mass and hence area must increase. Of course, we have been dealing with a spherically symmetric, static black hole, and throwing matter into it can easily violate both assumptions. Stephen Hawking generalised this result to something called the area theorem, which shows that the area of any type of black hole — not just a static, spherically symmetric one — can only increase with time, whatever physical process occurs.

You might be wondering why the reasoning for Schwarzschild black holes doesn’t apply to other black holes. If stuff can only go in, the mass of the black hole has to increase, and the area should increase, right? There are two reasons this doesn’t cut it. First, the total mass of an arbitrary black hole just isn’t well-defined. But more interestingly, even when it is, the relationship between mass and area can be non-trivial.

For instance, consider a spinning or Kerr black hole. It turns out you can extract energy from a spinning black hole using a slingshot maneuver called the Penrose process: a satellite which gets close to the black hole can get a kick to its angular momentum. Since the energy of the satellite increases, the energy and hence mass of the black hole decrease. But the area still increases! This implies an interesting relationship between the mass, area and angular momentum of the black hole, which we’ll say more about below.

The fact that area increases with time hints at a connection to entropy $S$. Entropy is the disorder of a system: the number of ways it could be while looking more or less the same. If the system evolves randomly (and big systems more or less do), it will tend to move towards states where there are more ways for it to be, a larger set of possibilities. This is captured in the second law of thermodynamics:

\[\delta S \geq 0.\]There are very few other quantities in physics that just get bigger, so Hawking suggested that there might be an analogy between entropy and horizon area.

3. Curvature and the zeroth law

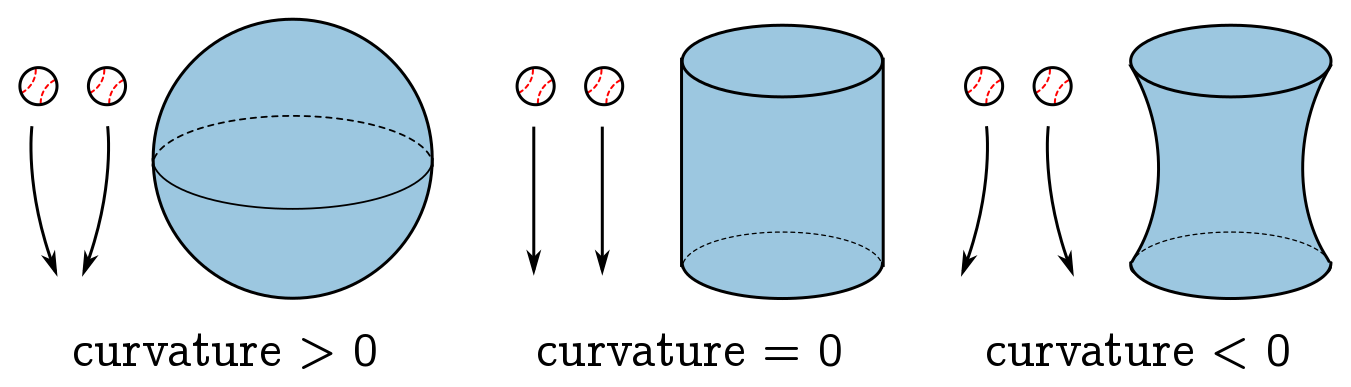

Another suggestive analogy comes from curvature. Curvature is a measure of gravitational tidal forces. It tells us how quickly two nearby, freely falling particles will move towards or apart from each other due to gravity.

Going back to the spherical black hole, symmetry tells us that the the curvature of space is the same at all points on the horizon at a given time. This is another property which generalises, but only to stationary black holes, that is, black holes which don’t change with time. Heuristically, we can think of the patches of the event horizon as interacting, pulling and pushing each other, and exchanging curvature. A stationary black hole is an equilibrium configuration for that exchange process, where the curvature is uniformly distributed.

Less heuristically, the curvature at the surface $\kappa$ can be defined as the force per unit mass the asymptotic observer (at infinity) must exert to suspend an object right at the black hole horizon. For this reason, the curvature at the horizon is called surface gravity.

If the surface gravity changes across the surface, then not only will space biscuits tend to accumulate at local maxima, but the horizon itself will respond. It can’t be stationary after all! We see the curvature exchange argument isn’t too far from the truth.

4. The laws of black hole thermodynamics

Curvature exchange is a loaded metaphor, designed to make you think of temperature. The interacting patches look like a thermal system equilibrating, and indeed, when the black hole is stationary this equilibration has finished.

That’s two analogies so far: area/entropy, and surface gravity/temperature. In 1973, Bardeen, Hawking and Carter collected a full set and presented them as the laws of black hole thermodynamics. The fact that surface gravity is constant for a stationary black hole is called the zeroth law, since the usual zeroth law states that temperature is constant for systems in thermal equilibrium. This suggests that the surface gravity $\kappa \propto T$, where $T$ is the temperature of the black hole.

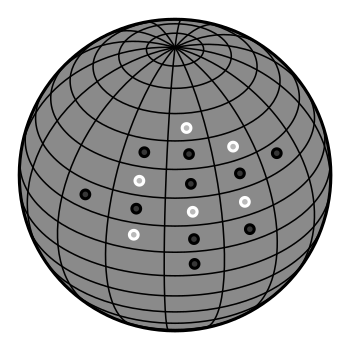

The second law of black hole thermodynamics is the area theorem: the horizon area increases in any physical process. This suggests that the entropy is proportional to the area, $A \propto S$. From Boltzmann’s law,

\[S = k_\text{B} \log N,\]where $N$ is the number of microscopic arrangement of a system with the same gross properties, we get a nice heuristic picture of the microstates of a black hole: divide the surface into cells, and assign a black or a white token. The number of ways of doing this gives the entropy!

To round things off, we still need black hole versions of the first and third law. The usual first law says that the change in the internal energy of a system equals heat gained plus work done on the system, or

\[dU = \delta Q + \text{work} = T\, dS + \text{work},\]where we used the thermodynamic definition of entropy: a small change in heat divided by the temperature at which heat exchange occurs, $dS = \delta Q/T$.

Thinking back to the example of the spinning black hole, a long calculation (with no classical analogue sadly!) gives a relationship between the change in mass $M$, area $A$ and angular momentum $J$:

\[dM = \left(\frac{\kappa}{8\pi G}\right) dA + \Omega \, dJ,\]where $\kappa$ is the surface gravity and $\Omega$ the angular velocity. This looks very similar to the first law! We have a change in energy on the left (since relativistically $E = Mc^2$) while the term $-\Omega \, dJ$ is precisely the work done by the system during the Penrose process, where angular momentum is converted into work. The remaining term has area and surface gravity appearing together, which are proportional to entropy and temperature. In fact, we note for future reference that

\[ST = \frac{\kappa A}{8\pi G}.\]We have a pretty compelling parallel!

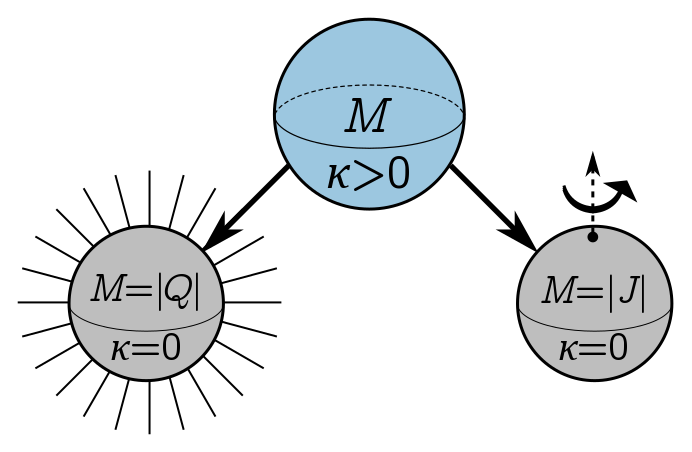

Finally, we need a version of the third law for black holes. The third law of thermodynamics is definitely the most obscure. In its strongest form, it states that the entropy of a system vanishes as the temperature goes to absolute zero. Based on what we already know about black holes, you might naively guess that the area of a black hole should vanish (the black hole shrinks to nothing!) as the curvature at the surface goes to zero.

This naive guess doesn’t quite work! There are objects called extremal black holes with vanishing surface curvature but nonzero area. The simplest way to get these black holes is to add electric charge or spin to an ordinary black hole, until you can’t add any more. But beware: the more charge or spin you add, the harder it gets. It becomes so hard, in fact, that you cannot build an extremal black hole from a non-extremal one in a finite number of steps!

This is reminiscent of a weaker form of the thermodynamic third law called the unattainability principle, which states that you can’t reduce a system to absolute zero in a finite number of steps. The surface curvature $\kappa$ of a black hole behaves in exactly the same way! We can now write down the full set of laws:

| Black holes | Thermodynamics |

|---|---|

| 0. $\kappa$ constant for stationary black holes. | 0. $T$ constant in equilibrium. |

| 1. $dM = (\kappa/8\pi G)\,dA + \Omega\, dJ$. | 1. $dU = T \, dS + \text{work}$. |

| 2. Area always increases: $\delta A \geq 0$. | 2. Entropy always increases: $\delta S \geq 0$. |

| 3. $\kappa\to 0$ takes infinite steps. | 3. $T\to 0$ takes infinite steps. |

In 1973, most people considered these laws to be a miraculous formal correspondence, and did not view black holes as genuine thermodynamic systems. The prominent exception is Jakob Bekenstein, who we will return to below. But in 1974, Stephen Hawking had a brilliant insight…

5. Hawking radiation

In 1974, Hawking realised that black holes really do have a temperature, and a blackbody spectrum to go with it. He famously calculated the Hawking temperature

\[k_\text{B} T = \frac{\hbar c^3}{8\pi GM},\]where $k_\text{B}$ is Boltzmann’s constant and $\hbar$ is Planck’s constant. Where does this come from? Hawking didn’t pull it out of thin air, but rather, spontaneously produced it from the vacuum. We will “derive” the result for a spherical black hole with extreme heuristic prejudice.

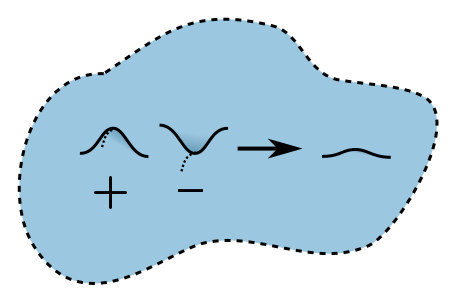

The usual analogy, which you may have heard before, is that pairs of virtual particles can pop into existence near the event horizon. One falls into the black hole, while the other zooms off with some energy $E$. The uncertainty in the energy of these spontaneously emitted photons tells us about the effective temperature of the black hole, since something cold has a narrow distribution of energies, while something hot has a broad distribution.

If you know a bit about statistical physics, you can make this analogy more precise. The blackbody distribution for a gas of photons is proportional to

\[f(E) = \frac{E^3}{e^{E/k_\text{B}T} - 1}.\]This drops off exponentially for $E \geq k_\text{B}T$, so we can approximate the uncertainty in the energy by

\[\Delta E = k_\text{B}T.\]But we can figure out $\Delta E$ a second way, using the uncertainty principle. These virtual photons can pop up anywhere on the horizon, so the uncertainty in position is the order the circumference of the black hole,

\[\Delta r = 2\pi r_\text{H} = \frac{4\pi GM}{c^2}.\]By Heisenberg’s uncertainity principle, the uncertainity in momentum is order

\[\Delta p \approx \frac{\hbar}{2 \Delta r} = \frac{\hbar c^2}{8\pi GM}.\]From special relativity, we know that the energy of the photon is $E = pc$, so we find the energy uncertainty

\[\Delta E = c \Delta p = \frac{\hbar c^3}{8\pi GM}.\]So, we guess the black hole has a temperature given by

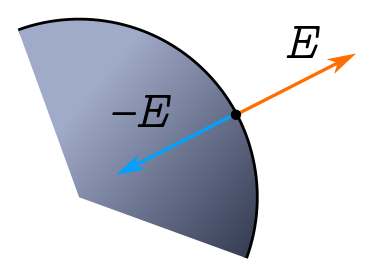

\[k_\text{B} T = \Delta E = \frac{\hbar c^3}{8\pi GM},\]in exact agreement with Hawking’s rigourous result! The upshot is that black holes are genuine thermal objects. But this leads to a puzzle: if black holes radiate, they can clearly lose energy and get smaller, violating the area theorem and hence the second law of black hole thermodynamics. What do we replace it with?

6. The generalised second law

To see how to generalise the second law, we first need to relate black hole and thermodynamic quantities, with constants of proportionality and all. It turns out that the surface gravity of a spherical black hole is simply related to the mass:

\[\kappa = \frac{1}{4GM}.\]We can plug this into Hawking’s result to get the long-awaited constant of proportionality between temperature and surface gravity:

\[k_\text{B} T = \frac{\hbar c^3\kappa}{2\pi}.\]With this in hand, we can work out the explicit expression for black hole entropy. From the first law, we know that $ST = \frac{\kappa A}{8\pi G}$, and hence

\[S_\text{BH} = \frac{\kappa A}{8\pi G T} = \frac{k_\text{B} c^3 A}{4 \hbar G}.\]This is the famous Bekenstein-Hawking entropy. Since it involves the four fundamental physical constants $\hbar, k_\text{B}, c, G$, something pretty profound is going on!

Prior to 1974, Bekenstein was the first person to really argue that the area could be interpreted as entropy; Hawking regarded $S \propto A$ as a formal analogy only. Bekenstein carefully thought about systems involving both black holes and ordinary thermodynamic systems, defining the generalised entropy as the sum of black hole entropy and ordinary entropy of matter systems outside the black hole. Bekenstein proposed the generalised second law, which states the generalised entropy should increase for any physical process:

\[\delta S_\text{gen} \geq 0, \quad S_\text{gen} = S_\text{outside} + S_\text{BH}.\]The generalised second law has many remarkable implications. In particular, it solves the puzzle raised earlier. Although the area of a black hole, and hence its entropy, decrease due to Hawking radiation, the total entropy of the universe increases. So although the area theorem is violated, the generalised second law is not.

The generalised second law also provides a sort of royal road for connecting the entropy of matter systems to their geometry. We will look at simplest such relation: the Bekenstein bound, which was in fact discovered by Bekenstein, thereby providing a counterexample to Sitgler’s law of eponymy. This gives a relationship between energy, size and entropy, and appears to be broadly true.

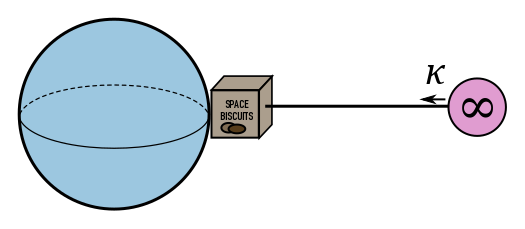

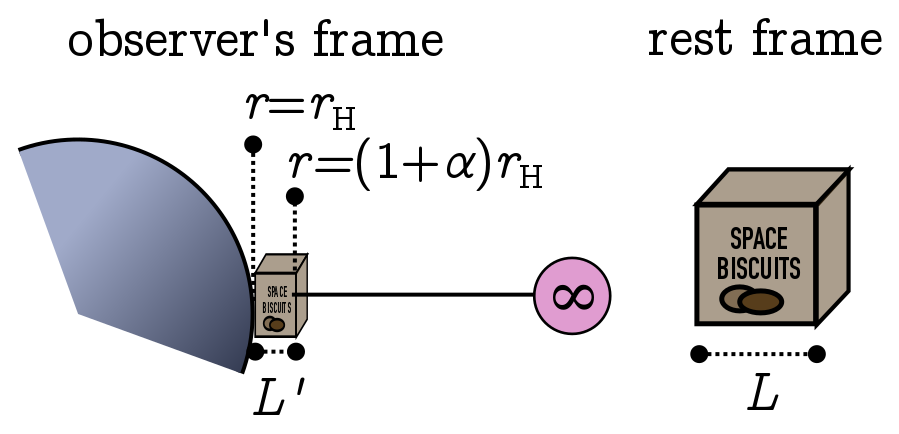

Imagine a small box of space biscuits, suspended above a spherical black hole of mass $M$ by the observer at infinity. The box has proper length $L$, and is held a proper distance $L$ above the horizon, and the observer measures the top of the box at $L’ = \alpha r_\text{H}$ for $\alpha \ll 1$. Since the light cones tip over near the horizon, local measurements of time and length differ from those at infinity, effectively described by a Lorentz factor $\gamma = 1/\sqrt{\alpha}$, with

\[L = \gamma L' = \sqrt{\alpha} r_\text{H},\]If the box has energy $E$, time dilation will lead to a reduction in energy, as viewed by the observer at infinity, with

\[E' = \frac{E}{\gamma} = \frac{LE}{r_\text{H}}.\]If the observer now drop the box into the black hole, the mass increases by the apparent energy of the box $\Delta M c^2 = E’$, so the new mass is $M’ = M + \Delta M$. But this changes the black hole entropy:

\[\begin{align*} S_\text{BH}' & \propto A' \propto {r'}^2_\text{H} \\ & \propto (M + \Delta M)^2 \\ & \approx M^2 + 2M\Delta M \\ \Longrightarrow \quad \Delta S_\text{BH} & \propto M\Delta M \propto LE. \end{align*}\]In fact, if you restore constants you can show that $\Delta S_\text{BH} = (4\pi k_\text{B}c/\hbar)LE$. If $S$ is the entropy of the box, we find that by dropping the space biscuits into the black hole, the change in generalised entropy is

\[\Delta S_\text{gen} = \frac{4\pi k_\text{B}c LE}{\hbar} - S.\]In order for this to be non-negative, we require

\[S \leq \frac{4\pi k_\text{B}c LE}{\hbar}.\]This argument involved a spherical black hole; more general arguments reduce the bound by a factor of $2$. But in any event, it appears that the size and calory content of a box of biscuits controls how many microscopic configurations it could be in!

7. Conclusion

We’ve just scratched the surface of black hole physics, and the many puzzles black holes present. But to my mind, the laws of black hole thermodynamics are the crowning achievement of the “Golden Age” of general relativity in the 60s and 70s. Hawking radiation and the generalised second law continue to provide surprises, and inspire developments in fields as diverse as quantum field theory, statistical mechanics and computer science, not to mention the search for a theory of quantum gravity.

I finish with a quote from the great astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar:

The black holes of nature are the most perfect macroscopic objects there are in the universe: the only elements in their construction are our concepts of space and time.

The laws of black hole mechanics hint at the possibility that black holes are microscopically perfect as well.