An equinoctial experiment

August 6, 2020. Eratosthenes measured the size of the earth using three data points: two shadows and the distance between them. During the vernal equinox in March, I performed a less elegant version of the same experiment and found the latitude of Vancouver. Lacking one data point, I invoke an imaginary friend in Whistler to help me.

Eratosthenes’ elegant estimate

Eratosthenes (276–195 BC) was head librarian at the Library of Alexandria, and one of the great thinkers of the ancient world. The library was destroyed by invading Roman emperors, and most of Eratosthenes’ work along with it. Thankfully, his elegant method for calculating the size of the earth using only the shadow of a stick survives.

On the summer solstice, locals in the Egyptian city of Syene noticed that, at noon, the sun hit the bottom of a deep well. Eratosthenes inferred that the sun must be directly overhead. He also knew from Egyptian surveyors that Syene was roughly $5000$ stadia (around $850 \,\mathrm{km}$) away from Alexandria. Eratosthenes performed a single experiment. At noon on the summer solstice, he measured the shadow of a vertical rod in Alexandria. He found it was roughly $1/8$ of the length of the rod. This is enough to estimate the radius of the earth!

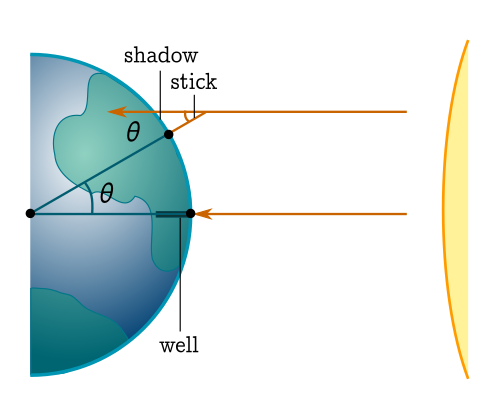

We assume the earth is spherical, and the sun far enough away that the arriving rays are parallel. The angle (in radians) the sunlight makes with the stick is

\[\theta = \tan^{-1} \left(\frac{\mathrm{shadow}}{\mathrm{stick}}\right) \approx \tan^{-1} \left(\frac{1}{8}\right) \approx \frac{1}{8},\]using the small angle approximation $\tan \theta \approx \theta$. We are also making the reasonable assumption that the shadow is small enough to be modelled as a straight line. From the diagram, we see that the angle the sunlight makes with the rod is the angle subtended by the arc of the great circle joining Alexandria and Syene. Since the the length of that great circle is the circumference of the earth, we have

\[\frac{\tan^{-1} \left(\frac{1}{8}\right)}{2\pi} \approx \frac{850 \,\mathrm{km}}{\mathrm{circumference}}.\]We rearrange and divide the circumference by $2\pi$ to estimate the radius:

\[\mathrm{radius} = \frac{\mathrm{circumference}}{2\pi} \approx \frac{850 \,\mathrm{km}}{1/8} = 6800 \, \mathrm{km}.\]The actual value is around $6300 \, \mathrm{km}$. Not a bad estimate from the shadow of a stick!

Can-do latitude

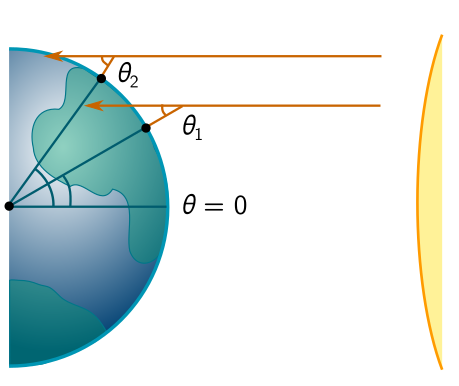

During the vernal equinox in March this year, I had a chance to do a similar experiment. The solstice—when Eratosthenes measured—is the time of year when the sun is furthest from the plane of the equator. The equinox is the opposite, with the sun passing through this plane. Thus, the rays coming in from the sun are (to a good approximation) parallel to the equatorial plane.

I realised, first of all, that measuring the sun at midday would give the latitude $\theta_1$ of Vancouver. This in itself is pretty neat! I just needed to measure the shadow of a stick, and Eratosthenes’ trigonometry would give me

\[\theta_1 = \tan^{-1} \left(\frac{\mathrm{shadow}}{\mathrm{stick}}\right).\]Even better, I could ask someone at a different location, say a distance $d$ north, to repeat the experiment and report their latitude $\theta_2$. For a small difference in angles $\Delta \theta = \theta_2 - \theta_1$ in radians, this would give

\[\mathrm{radius} = \frac{\mathrm{circumference}}{2\pi} \approx \frac{d}{\tan^{-1}(\Delta \theta)} \approx \frac{d}{\Delta\theta}.\]One subtlety is that midday is not usually the same as solar noon. There are fancy equations for dealing with this, but there are high-tech and low-tech shortcuts. The low-tech shortcut is to use a sundial (or just track the length of shadows and record the shortest), while the high-tech shortcut is the internet. I used the latter.

So, at solar noon, I walked down the street to discover that the day was cloudy and the shadows almost unuseable. I eventually found a newspaper box with a vague penumbra:

After some very coarse post-processing, I was able to make out the shadow, and drew the triangle above. It’s 137 pixels high and 120 wide, so

\[\tan \theta_1 \approx \frac{137}{120} \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \theta_1 \approx \tan^{-1}\left(\frac{137}{120}\right) \approx 48.8^\circ.\]The latitude of Vancouver is around $49.2^\circ$, so this is surprisingly good!

In fact, there’s a bit of luck here. I took this photo a few minutes after solar noon, and a few days after the equinox (March 23). Following the vernal equinox, the subsolar point (directly beneath the sun) begins to wander north, so that at solar noon the angle to the sun is decreased in the northern hemisphere. But shadows lengthen before and after noon. In this case, the two effects cancelled to produce a good estimate. It might be fun to estimate when I took the photo from the date and the angle!

Imaginary friend

Unfortunately, I don’t have a friend in Whistler I can call on to take random photographs of sticks. But as a theoretical physicist, it’s my prerogative to imagine I do. So, suppose my hypothetical friend in Whistler performed the experiment more carefully than I did, finding the shadow of some stick-like object at solar noon on the vernal equinox, and estimating a latitude of $\theta_2 \approx 50.1^\circ$. The resulting angular difference is

\[\Delta \theta = 1.3^\circ \approx 0.02.\]Given that Whistler is north of Vancouver by $d \approx 120 \text{ km}$, we get an estimate for the radius of the earth

\[\text{radius} \approx \frac{d}{\Delta \theta} = \frac{120 \text{ km}}{0.02} = 6000 \text{ km}.\]We did about as well as Eratosthenes! But I’ve been a bit slick. To give ourselves a more realistic range, let’s take $\theta_2 = 50.1\pm 0.3^\circ$. Then the range of estimates is

\[\text{radius} = 4300-6900 \text{ km}.\]The answer is in there somewhere. Given our cloudy data point, we’ve done okay!

Other experiments

There are a few extensions and alternatives. First of all, if I make a real friend in Whistler, we can perform this experiment whenever we want. Although the measured angles $\theta_{1,2}$ will no longer be latitudes, $\Delta \theta$ will be invariant provided we measure at the same time. There is also a beautiful method which involves a digital camera and a single vantage point, exploiting the (tiny) change in apparent size of the moon as it passes overhead. This requires you to know how big the moon is, but we can turn things around, and learn the size of the moon using the radius of the earth!

Another fun experiment is measuring shadows at the solstice. By comparing to the equinoctial result, this tells us the tilt of the earth on its axis! I forgot to do this in June, so I guess I’ll have to wait until December. We’ve only scraped the surface of practical applications of trigonometry, which (at the risk of sounding like your enthusiastic middle-school math teacher) I might write about more in future. But in the mean time, the autumnal equinox is a month and a half away (Sep 22), so you have plenty of time to prepare!