The Bloch sphere and Hopf fibrations

August 9, 2020. The Bloch sphere encodes the geometry of single qubit states. Remarkably, it is equivalent to the Hopf fibration of the 3-sphere! I prove this result and briefly touch on the generalisation to two and three qubits.

The Bloch sphere

A classical bit is either $0$ or $1$; if you prefer coins to computers, it’s heads or tails. A quantum bit, or qubit, is a complex linear combination of $0$ and $1$, considered as vectors:

\[|\psi\rangle = \alpha |0\rangle + \beta |1\rangle, \quad \alpha, \beta \in \mathbb{C}^2,\]where we’re using Dirac’s notation for vectors. A qubit is basically a quantum coin, with some probability of giving $0$ when we look at it, and a complementary probability of giving $1$. We would like to interpret $|\alpha|^2$ and $|\beta|^2$ as these probabilities, but for this to make sense, they must satisfy the normalization condition $|\alpha|^2 + |\beta|^2 = 1$. Writing this out in terms of the real and imaginary components $\alpha = a + ib, \beta = c + id$, we have

\[a^2 + b^2 + c^2 + d^2 = 1.\]This defines a sphere in four-dimensional space $\mathbb{R}^4$. The sphere itself has three dimensions, since it can be locally parameterised by $a$, $b$ and $c$. For this reason, we call it the 3-sphere $\mathbb{S}^3$.

There is one more ambiguity to worry about. Suppose that we rotate our qubit $|\psi\rangle$ by a phase, $e^{i\gamma}$. Just looking at this qubit by itself, this phase is unobservable, since the probabilities don’t change, i.e. $|e^{i\gamma}\alpha|^2 = |\alpha|^2$. We call this the global phase ambiguity, and identify

\[|\psi\rangle \sim e^{i\gamma}|\psi\rangle.\]This ambiguity identifies a circle of equivalent states on the 3-sphere. It seems likely the results of collapsing these circles will be a horrible mess. But a little miracle occurs, and you get a regular sphere! We’ll show this in an elementary way here, and do something more slick in the next section. The basic idea is to note that we can first fix the amplitudes $|\alpha|, |\beta|$, defining

\[|\alpha| = \cos\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right), \quad |\beta| = \sin\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right)\]for $\theta \in [0, \pi]$, with the range chosen to ensure the functions are positive. We can then choose the phase ambiguity so that $\alpha = |\alpha|$, leaving an arbitrary phase $\beta = e^{i\phi}|\beta|$. Thus, we have the following parameterisation of a qubit:

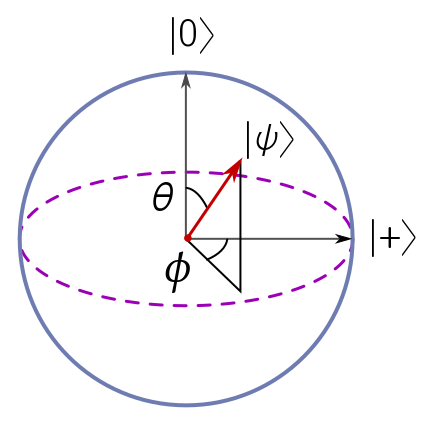

\[|\psi(\theta,\phi)\rangle = \cos\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right)|0\rangle + e^{i\phi}\sin\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right)|1\rangle,\]for $\theta \in [0,\pi]$ and $\phi \in [0,2\pi)$. These angles look a heck of a lot like spherical coordinates, so we draw them on a sphere, and call it the Bloch sphere.

A few states of interest are the north pole $|\psi(0,\phi)\rangle = |0\rangle$, the south pole $|\psi(\pi,\phi)\rangle = |1\rangle$, and the point on the equator of zero longitude,

\[\bigg|\psi\left(\frac{\pi}{2}, 0\right)\bigg\rangle = \cos\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)|0\rangle + \sin\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)|1\rangle = \frac{|0\rangle+|1\rangle}{\sqrt{2}} = |+\rangle.\]Now, is this really a sphere? Clearly, for fixed $\theta \in (0, 2\pi)$, we get circles due to the period of the complex exponential $e^{i\phi}$. So, at worst, we have a cylinder $[0, \pi] \times \mathbb{S}^1$. But the north cap of the cylinder degenerates into a single point, since $\sin 0 = 0$, leaving only $|0\rangle$ with no dependence on $\phi$.

At the south end, something subtler happens. Naively, we have a whole circle of points $e^{i\phi}|1\rangle$, but $e^{i\phi}|1\rangle \sim |1\rangle$ by residual phase ambiguity. Thus, we have a topological sphere (a cylinder with ends collapsed to points) on which we can introduce spherical coordinates. But geometrically, we instead appear to have a hemisphere

\[\alpha^2 + |\beta|^2 = a^2 + c^2 + d^2 = 1,\]for $\alpha \geq 0$. Is this really a sphere at all?

The Hopf fibration of $\mathbb{S}^3$

Let’s define the Hopf fibration in its full glory, and along the way, confirm the Bloch sphere is legitimately round when viewed correctly. For $(\alpha,\beta) \in \mathbb{S}^3$, i.e. satisfying our normalisation condition $|\alpha|^2 + |\beta|^2 = 1$, define the circle map

\[C(\alpha, \beta) = \overline{\alpha\beta^{-1}} \in \hat{\mathbb{C}},\]where $\hat{\mathbb{C}}$ is the Riemann sphere, i.e. the complex plane with a compactifying “hat” at infinity. The circle map tells us the image of a whole circle of equivalent states

\[(\alpha,\beta) \sim e^{i\gamma}(\alpha,\beta)\]on the Riemann sphere, since $C(e^{i\gamma}(\alpha,\beta)) = C (\alpha,\beta)$.

The canonical way to identify points on the Riemann sphere with points on the normal two-sphere $\mathbb{S}^2$ is stereographic projection. Basically, we think of $\mathbb{C} \simeq \mathbb{R}^2$ as a plane, place a unit sphere at the origin so it is sliced in half, and draw lines from points on the plane to the north pole of the sphere. Wherever they hit is the projection onto the sphere. In coordinates, the line from $\zeta = x + iy = r e^{i\phi}$ to $(0, 0, 1)$ is given by

\[\lambda \zeta + (1-\lambda)(0,0,1) = (\lambda x, \lambda y, 1-\lambda), \quad \lambda \in \mathbb{R},\]which intersects the unit sphere at

\[\lambda^2 r^2 + (1-\lambda)^2 = 1 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \lambda = \frac{2}{1 + r^2} \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \left(\frac{2x}{1 + r^2}, \frac{2y}{1 + r^2}, \frac{r^2-1}{1 + r^2}\right).\]The resulting coordinates $(\theta, \phi’)$ on the sphere are easily seen to be $\phi’ = \phi$ and

\[\cos\theta = \frac{r^2-1}{1 + r^2}.\]From the circle map, $\zeta = \overline{\alpha \beta^{-1}}$. If we choose the phase as before so that $\alpha = |\alpha|$ and $\beta = |\beta|e^{i\phi}$, we have $\zeta = e^{i\phi}|\alpha/\beta|$, and hence

\[\cos\theta = \frac{|\alpha/\beta|^2-1}{1 + |\alpha/\beta|^2} = \frac{|\alpha|^2 - |\beta|^2}{|\alpha|^2 + |\beta|^2} = |\alpha|^2 - |\beta|^2.\]Using $|\alpha|^2 + |\beta|^2 = 1$ and some trig identities, we reproduce the Bloch sphere map exactly:

\[\alpha = |\alpha| = \sqrt{\frac{1}{2}(1 + \cos\theta)} = \cos\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right), \quad \beta = \sin\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right) e^{i\phi}.\]But the circle map $C$, composed with (inverse) stereographic projection $p$, is precisely the Hopf map $\pi = p \circ C$:

\[\mathbb{S}^3 \overset{C}{\to} \hat{\mathbb{C}} \overset{p}{\to} \mathbb{S}^2.\]In other words, the Hopf map takes us from a point on the 3-sphere to the point its phase circle is “pasted” onto the 2-sphere. Since we can choose to embed the circle $\mathbb{S}^1$ into any class $e^{i\mathbb{S}^1}(\alpha,\beta) \subseteq \mathbb{S}^3$, we write the full fibration as

\[\mathbb{S}^1 \hookrightarrow \mathbb{S}^3 \overset{\pi}{\to} \mathbb{S}^2,\]where $\hookrightarrow$ is fancy math notation for “embed”. So, we see that the Hopf fibration is exactly equivalent to the Bloch sphere, and the Bloch sphere is indeed a sphere. In this case, we don’t have to degenerate caps by hand. We just had to choose the right set of coordinates!

Bloch chain

There are two other Hopf fibrations, i.e. ways of slicing up big spheres into little spheres pasted to a medium sphere:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbb{S}^3 & \hookrightarrow \mathbb{S}^7 \overset{\pi}{\to} \mathbb{S}^4 \\ \mathbb{S}^7 & \hookrightarrow \mathbb{S}^{15} \overset{\pi}{\to} \mathbb{S}^8. \end{align*}\]Somewhat marvellously, these correspond to descriptions of pure states of two and three qubits respectively. The state mappings are complicated for reasons I discuss below, but the fibrations generalise in a beautiful way from the 3-sphere case. A two qubit pure state is a complex linear combination of outcomes for two coin flips,

\[|\psi\rangle = \alpha|00\rangle + \beta |01\rangle + \gamma|10\rangle + \delta |11\rangle, \quad \alpha,\beta,\gamma,\delta\in\mathbb{C}.\]Once again, to intepret these as probabilities, we require

\[|\alpha|^2 + |\beta|^2+|\gamma|^2+|\delta|^2 =1,\]which restricts states to a 7-sphere $\mathbb{S}^7$. Here’s where things get fancy. To define the circle map above, we use a quotient of complex numbers. What we do now is turn our numbers $\alpha, \beta, \gamma, \delta$ into quaternions. The quaternions are a generalisation of complex numbers, where instead of having a single imaginary unit, we have real combinations of three imaginary numbers, $i, j$ and $k$. They obey some rules carved into a bridge by the great Irish mathematician William Hamilton:

\[i^2 = j^2 = k^2 = ijk = -1.\]Right-multiplying $ijk = -1$ by $k$, and using $k^2 = -1$, we learn that $ij = k$. Hence, if $\beta = a + bi$, then $\beta j = aj + bk$. Now, quaternions form a division algebra, in the sense that we can divide any element by any other. This is key to making the slicing work. Define

\[A = \alpha + \beta j, \quad B = \gamma + \delta j,\]with $\mathbb{S}^7$ given by $|A|^2 + |B|^2 = 1$. Since quaternions form a division algebra, we can define a 3-sphere map (instead of a circle map)

\[C_3(A, B) = \overline{AB^{-1}} \in \hat{\mathbb{C}}^2,\]where the complex conjugate is defined by flipping the sign of any imaginary unit, and we treat a quaternion as living in $\mathbb{C}^2$. We have added a point at infinity as before, in case we divide by zero. The circle map was constant on points related by a phase, or unit length complex number. The 3-sphere map is constant on points related by a unit length quaternion $Q$, i.e. $C_3(A, B) = C_3(AQ, BQ)$, where $Q$ is defined by

\[Q = Q_0 + Q_1i + Q_2j + Q_3k, \quad Q\overline{Q} = Q_0^2 + Q_1^2+Q_2^2 + Q_3^2 = 1.\]The components $Q_0, Q_1, Q_2, Q_3$ are real, so the unit quaternions live on a 3-sphere $\mathbb{S}^3$. Finally, we stereographically project using $p$ from $\hat{\mathbb{C}}^2$ onto a 4-sphere, and obtain the Hopf fibration

\[\mathbb{S}^3 \hookrightarrow \mathbb{S}^7 \overset{C_3}{\to} \hat{\mathbb{C}}^2 \overset{p}{\to} \mathbb{S}^4.\]The remaining Hopf fibration is similar. We flip three quantum coins, with a total of eight outcomes, or $16$ real parameters. Normalization reduces this to a 15-sphere of states. We proceed in a similar fashion, but replace quaternions with an even stranger object called octonions, with seven imaginary units. This is also a division algebra, and lets us define a 7-sphere map $C_7$ on the 15-sphere, with range $\hat{\mathbb{C}}^4$. We then stereographically project onto the 8-sphere. Thus, we obtain the final Hopf fibration:

\[\mathbb{S}^7 \hookrightarrow \mathbb{S}^{15} \overset{C_7}{\to} \hat{\mathbb{C}}^4 \overset{p}{\to} \mathbb{S}^8.\]This where the Hopf slicings stop! If we try to generalise to systems with more imaginary directions, they no longer form division algebras, so the circle map has no analogue.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, the relation to the pure states of two and three qubits is much messier. The reason is simple: global phase ambiguity is still a circle! The space of two- and three-qubit states is $7-1 = 6$ and $15-1=14$ respectively, where we subtract one to account for the one-dimensional circle of equivalent states we are identifying. This means the pure states are split between the base and the fibre, e.g. the $\mathbb{S}^3$ which is attached to each point of $\mathbb{S}^4$ in the case of two qubits.

The mapping is still interesting and potentially useful, but would take us too far afield to delve into. Check out the references if you’re interested! Because of this messiness, people justifiably say that the Bloch sphere has no analogue for more than one qubit. The whole truth—that the analogue exists, but is split across base and fibre of a particular choice of representation using hypercomplex numbers—is a bit of a mouthful!

References

- “Geometry of entangled states, Bloch spheres and Hopf fibrations” (2001), Rémy Mosseri and Rossen Dandoloff.

- “Two and Three Qubits Geometry and Hopf Fibrations” (2003), Rémy Mosseri.