Why is the sky blue?

December 31, 2020. Why is the sky blue? The conventional answer invokes Rayleigh scattering, but isn’t quite right! Here, we give a fuller answer, which involves a surprising combination of dimensional analysis, thermodynamics and physiology.

Wien’s law

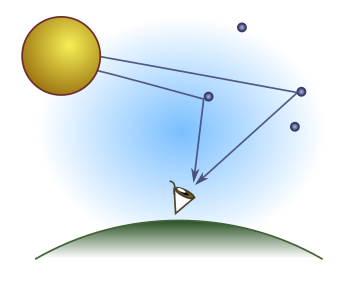

Raising your eyes on a sunny day, you will be confronted by one of those elemental mysteries of everyday life: the blueness of the sky. Why is it blue? Although this may be baby’s first physics question, the answer is a bit subtler than most physics textbooks make out. The first qualitatively correct explanation is due to Leonardo Da Vinci, who realised that blue is not the colour of the air itself, but rather, light reflected by air. He wrote that

….the blueness we see in the atmosphere is not intrinsic color, but is caused by warm vapor evaporated in minute and insensible atoms on which the solar rays fall, rendering them luminous against the infinite darkness of the fiery sphere which lies beyond and includes it…

In other words, space is black, and without intrinsic colour. Air reflects the light of the sun, and appears blue. If air reflected all solar light equally, it would appear the same colour as the sun. It’s a bit hard to tell what colour the sun actually is, since it’s so blindingly bright. The simplest measure is to see what wavelength it emits most, $\lambda_{\text{max}}$. We can guess this wavelength based on dimensional analysis.

The surface temperature of the sun is around $T = 5800 \text{ K}$, and the hot atoms at its surface emit light. The relevant physical constants are Boltzmann constant $k$ (since temperature is involve), Planck’s constant $h$ (since atoms are involved), and the speed of light $c$ (since light is involved). We want a wavelength $\lambda$, so we guess a relation of the form

\[\lambda_{\text{max}} = h^a c^b k^d T^e\]for some powers $a, b, d, e$. Let $\mathcal{T}$ be the dimension of time, $E = ML^2/\mathcal{T}^2$ dimensons of energy and $\Theta$ the dimension of temperature. Then our constants have dimensions $[h] = E\mathcal{T}$, $[c] = L/\mathcal{T}$, $[k] = E/\Theta$, and hence

\[L = [\lambda_{\text{max}}] = [h^a c^b k^d T^e] = E^{a+c} \mathcal{T}^{a-b}L^b \Theta^{d-c}.\]Since $M$ only appears in $E$ (on the RHS), we obtain the equations

\[a+c = 0,\quad a- b = 0, \quad b = 1, \quad d - c = 0,\]with solution $a = b = -c = -d = 1$. Our dimensional guess is then

\[\lambda_{\text{max}} \sim \frac{hc}{kT}.\]Up to dimensionless numbers, this is called Wien’s law. The important point is that the dominant wavelength is inversely proportional to temperature! If we would like to include dimensionless numbers, then as shown in the appendix, we have

\[\lambda_{\text{max}} \approx \frac{hc}{5kT}.\]If we substitute in constants and the surface temperature of the sun, we get in SI units

\[\lambda_{\text{max}} \approx \frac{(6.6 \times 10^{-34})(3 \times 10^8)}{5(1.4 \times 10^{-23})5800} \text{ m} \approx 480 \text{ nm}.\]This is right on the cusp between blue and green. You may not have known that the sun is bluey-green, since when you look at it without burning a hole in your retina, it appears yellow! This is precisely because of the blue light subtracted by scattering from the air. But this subtraction doesn’t quite add up. If the air took on the dominant colour of the sun (thereby making it yellow), we would expect the sky to be bluey-green rather than azure blue. What are we missing?

Rayleigh scattering

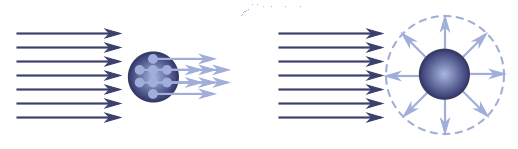

We are missing the fact that air is partial to scattering some kinds of light more than others. To see how molecules interact with different colours, we’ll repeat a famous dimensional analysis due to Lord Rayleigh, aka John William Strutt. The wavelength of visible light is a few hundred nanometres, a thousand times larger than an air molecule. Thus, if an incoming light wave of amplitude $A_{\text{in}}$ excites an air molecule, all the different parts of the molecule should oscillate in phase. These oscillations will coherently add together due to the phenomenon of superposition, and we expect the amplitude of the outgoing, reflected light $A_{\text{out}}$ to be proportional to the number of elementary oscillators. This is pictured below left.

The number of elementary oscillators should be proportional to the volume of the molecule, $V$. But since the molecule is small, the outgoing wave spreads spherically outward, as depicted above right, and conservation of energy requires that the intensity $I_{\text{out}}$, or energy per unit area, obeys an inverse square law:

\[4\pi r^2 I_{\text{out}}(r) \propto r^2 A^2_\text{out} = \text{const} \quad \Longrightarrow \quad A^2_\text{out} \propto \frac{V^2}{r^2}.\]We also guess that the output intensity $I_{\text{out}}$ is proportional to the input intensity $I_{\text{in}} = A^2_{\text{in}}$. Thus, we guess a relation of the form

\[I_{\text{out}}(r) \propto I_{\text{in}} \cdot \frac{V^2}{r^2}.\]But notice that the right-hand side is not dimensionally equal to the left, since we have units of intensity on the LHS, and on the RHS, intensity times $[V^2/r^2] = L^4$. To get rid of this, there is only one other quantity with dimensions of length left: the wavelength $\lambda$ of light itself! Dividing by $\lambda^4$ gives the famous formula for the intensity of Rayleigh scattering:

\[\frac{I_{\text{out}}}{I_{\text{in}}} = \frac{CV^2}{r^2\lambda^4},\]for a dimensionless constant $C$. This leads to the common explanation of the colour of the sky. Blue light has a shorter wavelength than red, so it is scattered more by air molecules, creating that pure azure we know and love. But does it? This explanation would make sense if blue was the shortest visible wavelength, but indigo and violet (after the ‘B’ in ROYGBIV) have even shorter wavelengths. So why isn’t the sky violet?

The eyes have it

To determine the dominant colour of the sky, we need to consider the spread of light arriving from the sun, and then multiply by $1/\lambda^4$ to account for Rayleigh scattering. The dominant colour is the highest point on this curve, analogous to Wien’s law. We do this in the appendix. The result is

\[\lambda \approx \frac{hc}{9kT} \approx 270 \text{ nm}.\]This isn’t a visible wavelength at all! It’s in the ultraviolet. Assuming that the curve drops smoothly, this seems to suggest that the strongest visible wavelength should be violet. So once again, we can ask: why is the sky blue?

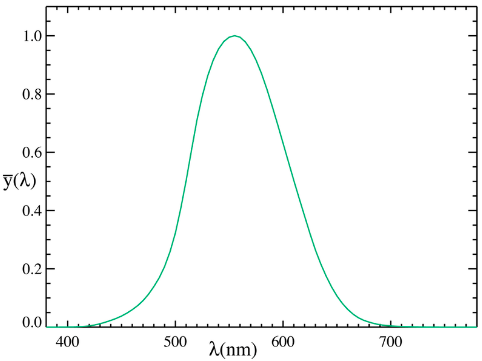

The answer is that our eyes are much more sensitive to blue than to violet. The sensitivity of the human eye to different colours is described by something called the photopic curve, which peaks around $\lambda = 550 \text{ nm}$ (yellow), and drops rapidly away until almost vanishing at $400 \text{ nm}$ (violet) at one end, and $700 \text{ nm}$ (dark red) at the other. If we take a product of all three functions, we get an effective spectrum:

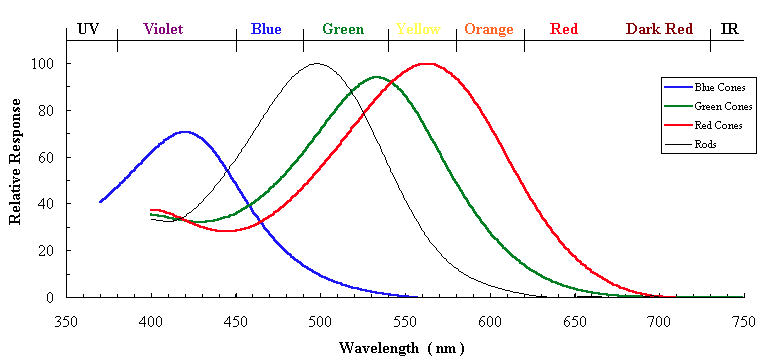

\[\text{effective spectrum} = \text{solar spectrum} \times \text{Rayleigh scattering} \times \text{photopic curve}.\]So, surely the peak here should be blue. Right? Well, it turns out (calculation omitted) that this effective spectrum peaks in the green! We need to think a bit more about the physiology of the eye. The photopic curve is actually an average over three different types of receptor cells, called cones, responsible for colour vision. There are short cones (S) which are sensitive to blue, medium cones (M) sensitive to bluey-green through to yellow, and finally, long cones sensitive to orange through red. The response curves, including relative strength, are shown below, from this page by Eric Toolson:

The averaged curve peaks where the medium and long curves overlap, but most of the scattered light from the sun hits the short cones. There is, however, a dash of green in there, making the cerulean blue of the sky, with an effective dominant wavelength of around $450 \text{ nm}$.

We now have our (relatively sophisticated) answer to our original question: why is the sky blue? The sun emits a range of wavelengths peaked in the bluey-green. Shorter wavelengths are more likely to bounce off air molecules, due to the $1/\lambda^4$ scaling of Rayleigh scattering, so the violet end of the visible spectrum is heavily preferenced. Finally, the short cones responsible for seeing blue are more heavily activated than the medium and long cones, so the sky is azure: primarily blue with a hint of green. For more discussion, check out Craig Bohren’s wonderful review of atmospheric optics.

Appendix: a transcendental approximation

To a good approximation, the sun is a perfect emitter of light, with a blackbody spectrum for intensity per unit wavelength

\[R_5(\lambda, T) = \frac{A_5}{\lambda^5} \frac{1}{e^{h c/kT\lambda} - 1}.\](You can find a derivation in any textbook on thermodynamics, or simply take it on faith.) Wien’s law arises from finding the peak of this curve. Similarly, the colour of the sky (independent of the human eye) arises from maximising this spectral curve, multiplied by the Rayleigh scattering term $\lambda^{-4}$:

\[R_9(\lambda, T) = \frac{A_9}{\lambda^9} \frac{1}{e^{h c/kT\lambda} - 1}.\]Let’s define $x = h c/kT\lambda$. We can solve both problems by defining a general function $R_n(x) \propto x^n/(e^x- 1)$ and determining approximately where it peaks. We use the first-year calculus approach of differentiating and setting the derivative to zero:

\[f'_T(x) \propto \left[\frac{nx^{n-1}}{e^{x} - 1} - \frac{x^n e^x}{(e^x - 1)^2}\right] = 0 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad (x^* - n) e^{x^*} + n= 0.\]This is a transcendental equation with no closed-form solution. But since the exponential grows very quickly, we expect that the term $y = x^* - n$ multiplying it must be small. Let’s rewrite our equation terms of $y$:

\[y e^y + e^{-n} n = 0.\]We then Taylor expand $e^y$. For something tractable, we just go to first order in $y$:

\[0 = y e^y + e^{-n} n \approx y(1 + y) + e^{-n}n.\]The quadratic formula gives the self-consistently small solution

\[y = \frac{1}{2}\left(\sqrt{1 - 4n e^{-n}} - 1\right) \approx - n e^{-n},\]where we used the binomial approximation. So the maximum wavelength is roughly

\[x^* = y + n \approx n(1 - e^{-n}) \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \lambda^* \approx \frac{h c}{kT n(1 - e^{-n})} \approx \frac{hc}{kT n}.\]This gives the approximate maxima above.