The endless present

July 29, 2019. Modern physics suggests a view of time called four-dimensionalism: just as all places exist simultaneously, all times should exist simultaneously. I examine some consequences for the psychology of time, and contrast with the (more intuitive but ultimately incoherent) philosophy of time called presentism.

Introduction

If physics is to be believed, there is nothing special about the present. “Right now” is similar to the statement “right here”, but it refers to when the speaker is. But what is privileged about the moment of utterance? Is it any more privileged than the bath tub or the park next to the subway where the speaker happens to declare they are located? In physical terms, the “present” is just a projection function:

\[P(t, x, y, z) \mapsto t.\]On the other hand, time feels different from space. Unlike space, where I can travel at will between the park and the bath tub, I cannot choose to return to last Tuesday. We seem to go in one direction through time, at a fixed speed. Of course, physics does not contradict this. Relativity teaches us that time is, indeed, different from space, and closely bound up with causation. Since experience is a causal affair, with earlier brain states influencing later ones and not the other way round, this is as it should be.

But there is more to the peculiar psychology of the present. While the direction of our movement through time is easily explained, the sensation of being in a particular moment takes more work. Our qualia seem to be attached to now; there is a folk Cartesian argument which takes this as incorrigible proof that the present is special and perhaps the only “time” which really exists. This view is called presentism.

I will argue below that, despite its folk appeal, presentism is not a viable metaphysics of time. Nevertheless, there is an explanatory gap between common psychological experience and four-dimensionalism. I will argue that the gap can be filled by thinking carefully about how sensation arises from brain states. Ultimately, we will need to resolve a variant of Zeno’s arrow paradox. Zeno asked: how can we explain the motion of an arrow from its “stationary” time slice? Similarly, we must ask what properties of a brain state explain the sensation of moving through time.

No time like the present

I’ll recap some properties of time, before defining (and arguing against) presentism. This will leave us with some folk psychology to explain!

Simultaneity and causal order

Einstein taught us that simultaneity is relative. Any time two observers move relative to each other, they will disagree about which events occur at the same time. However, whatever your reference frame, you will get the same answer for the following quantity:

\[s^2\big(P(t_1,\vec{x}_1), Q(t_2,\vec{x}_2)\big) = - (t_1-t_2)^2+|\vec{x}_1-\vec{x}_2|^2.\]Here, $P$ and $Q$ are points in spacetime, and $(t, \vec{x})$ are spacetime coordinates in an inertial (non-accelerating) reference frame. The point is that, by virtue of the principle of relativity, whatever reference frame we use to define the coordinates, the function $s^2$, called the invariant spacetime interval, is the same.

The spacetime interval has the follow physical interpretation:

- If $s^2(P, Q) = 0$, and $t_1 < t_2$ ($t_2 < t_1$), then $P$ and $Q$ are null-separated, and we can send a light ray from $P$ to $Q$ ($Q$ to $P$).

- If $s^2(P, Q) < 0$, and $t_1 < t_2$ ($t_2 < t_1$), then $P$ and $Q$ are timelike-separated and a massive observer, or message, can travel from $P$ to $Q$ ($Q$ to $P$).

- If $s^2(P, Q) > 0$, then $P$ and $Q$ are spacelike-separated, and cannot influence each other causally.

Note that the time-ordering in the first two cases does not change, whatever the reference frame. For instance, if $t_1 < t_2$, then $t_1’ < t_2’$ in any other inertial reference frame. But for spacelike separated observers, the ordering of $t_1$ and $t_2$ does depend on the frame. This is precisely the relativity of simultaneity! Since the order of events is frame-dependent for these observers, if I want to ensure that cause and effect are ordered monotonically, we have to demand that spacelike separated observers cannot influence each other.

But why should cause and effect be ordered? The simple answer is that reverse causation gives rise to time travel and all its attendant paradoxes. For instance, imagine I could send messages faster than light, the requisite condition to influence spacelike separated observers. It is easy to set up a situation where, bouncing signals off a moving mirror, I can communicate with myself in the past. More dramatically, I could send a signal to a bomb in the past which blows up the machine sending the message before it can send the signal! To me, this suggests that the ordering of cause and effect is a basic consistency requirement for the universe.

If you want to be a little more precise about cause and effect, you can use the spacetime interval to define a partial order $\prec$ on events. If $P$ can influence $Q$ (they are either null- or timelike-separated), we write $P \prec Q$, and note that this relation is

- reflexive, $P \prec P$;

- antisymmetric, $P \prec Q$ and $Q \prec P$ implies $P = Q$; and

- transitive, $P \prec Q$ and $Q \prec R$ implies $P \prec R$.

Two points are not comparable, or causally ordered, just in case they are spacelike separated. Note that $\prec$ captures the possibility of causal influence, rather than actual causal influence. In principle, I can write letters to (causally influence) my neighbour’s dog, but I choose not to.

Presentism defined

What has this got to do with the present? If I understand the notion properly, presentism is the view that only some time slice of the universe really exists. By “time slice”, I mean some collection of events $\Sigma$ which are mutually spacelike separated, or equivalently, mutually incomparable according to the causal partial order. I used to think that the relativity of simulaneity was knock-down argument against presentism. Since being simultaneous is not transitive, and the notion of being co-present (existing together) surely is transitive, isn’t presentism obviously wrong? No: all this shows is that being co-present is not the same as being simultanous according to each other’s clocks. If we define the “present” as a slice $\Sigma$, we will have a transitive notion of co-presence after all.

One issue with $\Sigma$ is that it is not unique. That is, any event $P$ is contained in an infinite number of spacelike slices $\Sigma$. Which is the “real” one? At large scales, our universe has a preferred cosmological time $t$, and perhaps (the presentist could argue) this naturally singles out a slice $\Sigma(t)$. This solution is somewhat ad-hoc, but more importantly, doesn’t explain how to “pick out” the right slice locally, for instance in the presence of a black hole. Perhaps a space bungee expedition goes horribly wrong, and as my friend falls through the event horizon, I wonder “When are they now? Which slice is real?” I don’t think the presentist can help, since the natural operational definitions (e.g. I can send a message to the slice) are causal, and therefore take me out of the set of timelike slices $\Sigma$. (In fact, in the presence of a black hole there can be global obstructions to the definition of $\Sigma$, but I will ignore these. My objections to presentism do not depend on exotic features of spacetime.)

One suspects that, in asking these questions about the space bungee accident, language has “gone on holiday” (Wittgenstein). But the presentist can simply assert that the slice exists, and leave the problem of selecting the correct $\Sigma$ to the axiom of choice, or God, or some comparable higher power. What can we say then?

Incompetent demiurges

A subtler problem is change. Presentism claims that what is real, i.e. the present slice $\Sigma$, is changing. But changing with respect to what? If I label or define slices with respect to some type of “universal proper time” $\lambda$ (e.g. cosmological time), the answer seems to be: with respect to $\lambda$, at a rate of 1 unit of $\lambda$ per unit of $\lambda$. This is just the old joke that we are moving into the future at 1 second per second.

The answer is of course tautological. But it is worse than that for the presentist. To see why, let’s discretise time into steps $t_n$. Presentism suggests that, ontologically, a slice $\Sigma(t_0) = \Sigma_0$ is brought into being, then destroyed and replaced by $\Sigma_1$. We repeat the process with $\Sigma_2$, and so forth. How long do these slices exist? It seems like there is no way to measure this, since $t_n$ is attached to the slices themselves. But to ask what exists “now” presupposes some sort of time in our creation and destruction process!

We have the following infinite regress problem. Suppose a demiurge $D_1$ is running this “program” of creating and destroying the slices $\Sigma_n$. To even ask which slice is currently loaded, the demiurge also needs to have a time $t^{(1)}$ (once again discrete for simplicity). But of course, we then need another demiurge $D_2$ with time $t^{(2)}$ to program the slices for the demiurge $D_1$. And so on. I think this a bad infinite regress since no demiurge grounds what “present” actually means. Perhaps, like the choice of spacelike slices, the presentist can appeal to God (Dei or $D$), in this case as a sort of limit or union of demiurges, $D = \lim_{n\to\infty} \cup_n D_n$.

I don’t think this helps, but let us suppose for the sake of argument that it is possible to fix the regress. What if our demiurges make errors, as demiurges are wont to do? Perhaps the slices $\Sigma_4$ and $\Sigma_5$ are both loaded at some time $t^{(1)}$, or different slices of the demiurge itself coexist due to a “momentary lapse” by one of its superiors. Even worse, demiurges could get the order wrong, making $\Sigma_9$ before $\Sigma_3$. Can observers living in $\Sigma$ tell how long in demiurge time the slice is running for? Or somehow feel “present” in both $\Sigma_4$ and $\Sigma_5$ when they are run at the same time? Or “sense” the reversal of causal order when $\Sigma_3$ comes before $\Sigma_9$?

Of course not. Observers living in $\Sigma$ have no access to any of this data, since this would give them super-causal powers. We cannot tell what any demiurge is doing, including $D_1$. The ability to tell which slice is present, how long it is run for, or its “demiurgic” order relative to other slices, is unreasonably powerful for a creature confined to the causal partial order $\prec$. In other words, even if presentism is a correct picture of the ontology of time, there is every reason to think that we would be unable to distinguish this state of affairs from the more conventional, four-dimensional picture where all the slices $\Sigma_n$ exist at the same time.

(These incompetent demiurges are partially inspired by Greg Egan’s “dust theory”, from his excellent novel Permutation City. The demiurge argument has a similar flavour to Augustine’s argument against duration in the Confessions.)

Brain states and sensations

Perhaps, as I have argued, presentism is not a sensible picture of time. But the claims of our qualia are not lightly dismissed. An infinite tower of demiurges creating and destroying one another may be absurd, but the related convictions that I am experiencing right now, and that change is real, are not absurd. How can we explain these in the framework of four-dimensionalism?

Experience and “nowness”

Conscious experience is famously difficult to explain from the physicalist viewpoint. But whatever qualia are, I assume they are the result of physical processes in the brain, and supervene on brain states. Run the process, or set up the state (a subtle distinction we return to later), and the associated conscious experience should appear.

It is then straightforward to explain why we feel like we are always “in the present moment” from the four-dimensionalist perspective. If the time slice of the brain $B(t_n) = B_n$ always exists, it is always in a particular state; it is therefore always producing the sensations $S_n$ associated with that state. Of course, those sensations are attached to a specific time and place, and the sensation of “experiencing things right now” is no different, fundamentally, from “experiencing things right here”. The novelty or strangeness of these time indexicals is that we do not feel like we control our motion in time, so there is perhaps something surprising about being “at this present moment”. How did we get there? It was not an act of will, like walking from the bath tub to the station. But neither was it some deep ontology that our brains are somehow magically enabled to track. It is simply a result of causal relations between brain states.

Before I elaborate on this last statement, let me be clear. I think that brain states $B_n$ always exist; this is what four-dimensionalism dictates. If they always exist, they are always producing the associated qualia $S_n$ and so a brain state leads to a permanent state of feeling. You may ask how it is possible to always be “feeling” $S_n$ when the sensations feel temporary. The point of the faulty demiurges is that the ontology of time slices has nothing to do with conscious experience. This is why presentism is tempting but wrong. It conflates properties of conscious experience with properties of time.

The arrow of Zeno

It is not clear that brain states that are permanently feeling have anything to do with our everyday experience. Sensations last a moment, and are quickly succeeded by new ones, almost as if they are being created and destroyed by particularly reliable demiurge. The question, then, is whether the content of the sensation $S_n$ can account both for the feeling of duration and succession.

There is a helpful pre-Socratic analogue to the problem we are considering here. Zeno’s third paradox of motion involved an arrow in flight. We can state the paradox as follows:

- At any moment of time, the arrow is stationary.

- Time is composed of moments.

- Stationary objects remain stationary.

- Hence, the arrow can never move.

Similarly, one might imagine that a brain state $B_n$, always producing the qualia $S_n$, can never give rise to the “flow” of conscious experience. (A similar argument was put forward independently by Le Poidevin, building on Broad’s Scientific Thought.)

The answer to the third paradox is simple. There is a difference between a stationary arrow and a moving arrow examined at an instant of time. The moving arrow has real properties – velocity, momentum, kinetic energy – the stationary arrow lacks. These not only explain the difference in subsequent motion but have measurable effects on the slice itself, e.g. the arrow is heavier by virtue of Einstein’s famous formula $E = mc^2$.

Similarly, intrinsic properties of the brain state $B_n$ must generate the feelings of duration and succession. Let’s first consider succession. At a physical level, “succession” reflects the fact that earlier brain states $B_{m<n}$ are part of the causal input to the brain state $B_n$. The previous states $B_{m<n}$ are in fact stored and represented in $B_n$ via memory, but at an abstract level, succession is just the statement that causal relations are mirrored in cognitive ones. The time slices of the arrow are close to each other, as dictated by causality.

Duration is trickier, but not so different from the arrow’s velocity. The velocity is the rate at which the arrow acquires distance. But I cannot tell you the velocity without specifying some units to measure distance and time, i.e. a physical basis of comparison. The old saw goes: how long is a piece of string? One can only answer by producing another piece of string.

It seems likely that “mental velocity” through time, and the sense of the duration of the present moment, are connected to the rate of acquisition of sensation. Like the moving arrow, a “mental velocity” cannot make sense without units. Luckily, our brains are equipped with a bevy of physiological processes which can be used to measure time (circulation, transduction networks, and so forth), along with input channels whose thresholds and capacities can measure the amount of sensation. It seems plausible that the subjective rate of experience is some function of the strength, nature and speed of sensory input, relative to these physiologically defined units of measurement and how efficiently they can stored in memory.

The identity wave train

The sense of succession and time’s flow are not merely of phenomenological interest, but deeply bound up with the way we think about personal identity. A life, it seems, is a state of mental flux which is created at birth, has some experiences, and is destroyed at death. “Present David” undertakes actions (e.g. exercising) on the understanding that “future David” will benefit, and congratulates himself for the beneficial actions of “past David”, like flossing his teeth. The current slice expects to become the future slice, and believes it was once the past slice.

But the four-dimensional perspective suggests that no slice ever turns into any other. They all exist, separately and simultaneously, stuck in some sort of Nietzschean loop, or more accurately, a continuous wave train of experience which is always oscillating. But in waves, the oscillating medium does not itself need to move to transmit energy, and by analogy, we can transmit a sense of identity forward in time with individual mental slices that are temporally fixed.

Instead of viewing personal identity as a changing mental state, it is the thing transmitted by the states. What exactly is transmitted is a complicated and different question; all we have done is tweak the metaphysical parameters of that debate. I am still connected by the chains of causation to past and future David, even if the current mental slice was not originally one, and bound to become the other.

Conclusion

To reconcile our experience of time with four-dimensionalism, we seem to be driven to some strange conclusions. Every brain state $B_n$ in the history of a thinking being always exists, by four-dimensionalism. If we are physicalists about sensation, then those brain states are always accompanied by sensations. The brain states always feel. But “always feeling” does not mean “feeling always”. We should not confuse the properties of the time slices with properties of the sensations they give rise to (fallacy of composition). This is the fundamental error of the presentist.

Four-dimensionalism therefore suggests an extreme version of Nietzsche’s doctrine of eternal recurrence: we are, and will always, live all moments of our life simultaneously. These brain states are tied together coherently, like the oscillating particles in a wave, and transmit a sense of personal identity into the future.

I find it comforting to think that death is not the final and irrevocable destruction of my brain slice, but just another point on the worldline. Then again, I suppose that all our experiences, good and bad, will be preserved like some sort of experiential jam which someone is forever in the act of tasting. We should consider carefully what flavours we choose.

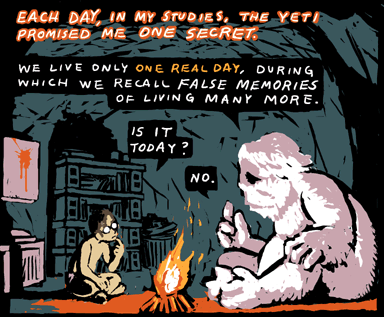

Postscript: “Arrest”

For a different take on these issues, see my sci-fi short story “Arrest”. It was originally submitted to the Ubyssey sci-fi competition 2019.

References

- Permutation City (2007), Greg Egan.

- “Zeno’s Paradoxes” (2018), Nick Huggett. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- “The Experience and Perception of Time” (2019), Robin Le Poidevin. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- “Personal identity” (2015), Eric Olson.