A simplicial generalisation of the Bloch ball

February 5, 2021. I explore unitary orbits of density matrices for finite-dimensional quantum systems. The upshot is a neat scheme for representing orbits using simplices.

Introduction

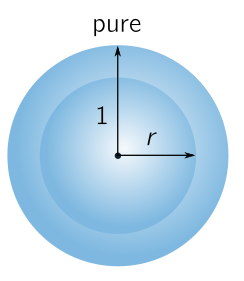

The Bloch sphere represents the space of pure states on a single qubit (see also this recent post). The “Bloch ball” is the space of all density matrices on the qubit. It fills in the Bloch sphere with concentric spheres of increasing mixedness, and at the centre is the maximally mixed state $I_2/2$, where $I_d$ will denote the $d \times d$ identity matrix.

Spheres arise naturally. They carry the structure of the unitary group $\mathrm{U}(2)$ acting on qubits, once we have modded out by the phase ambiguity:

\[\frac{\mathrm{U}(2)}{\mathrm{U}(1)} = \mathrm{SU}(2).\]This is a double cover of the rotation group $\mathrm{SO}(3)$, which acts transitively on the sphere. (The “double cover” part gives us spinors.) Thus, spheres occur naturally as unitary orbits, and indeed, each concentric sphere in the Bloch ball is such an orbit. The question is whether this generalises nicely to higher dimensions.

The Bloch ball

Let’s think about the Bloch ball in a little more detail. Each density matrix $\rho$ is a $2\times 2$ matrix acting on the space of qubits, which is positive and has unit trace. Positivity just means that, for every state $|\psi\rangle$,

\[\langle \psi | (\rho | \psi \rangle) \geq 0.\]Hence, $\rho$ is Hermitian, since the reality of this inner product implies

\[\langle \psi | (\rho | \psi \rangle) = (\langle \psi | \rho^\dagger) |\psi \rangle \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \rho = \rho^\dagger.\]In turn, this means that $\rho$ is unitarily diagonalisable, i.e. $U^\dagger \rho U = \Lambda$ for some diagonal matrix $\Lambda$ and unitary matrix $U^\dagger U = UU^\dagger = I$. It’s also clear these eigenvalues must be positive. In fact, since the permutation matrices are unitary, we can arrange the eigenvalues in decreasing size, so that every $2 \times 2$ density matrix is unitarily equivalent to some matrix

\[\Lambda(p) = \begin{bmatrix} p & \\ & 1-p \end{bmatrix}\]for $p \in [1/2, 1]$. The maximally mixed density $I_2/2$ has a trivial orbit, since it always gets mapped to itself:

\[U^\dagger I_2 U = U^\dagger U = I_2.\]We can measure the distance from this matrix to $\Lambda(p)$ using the Frobenius norm, aka Hilbert-Schmidt norm. This is just the usual vector norm where we treat a matrix $A = [a_{ij}]$ as a big vector:

\[||A||^2 = \sum_{ij} |a_{ij}|^2 = \mbox{Tr}[A^\dagger A].\]Hence,

\[\begin{align*} ||\Lambda(p) - \tfrac{1}{2}I_2||^2 & = \left|\left| \begin{bmatrix} p - 1/2 & \\ & 1/2-p \end{bmatrix} \right|\right|^2 \end{align*} = 2\left(p - \tfrac{1}{2}\right)^2.\]It’s easy to see that any density matrix in the unitary orbit of $\Lambda(p)$ has the same distance, since we can use $I_2 = U^\dagger I_2 U$, i.e. it is a class function:

\[\begin{align*} ||U^\dagger \Lambda U - \tfrac{1}{2}I_2||^2 & = \mbox{Tr}\left[(U^\dagger \Lambda U - \tfrac{1}{2}I_2)^\dagger (U^\dagger \Lambda U - \tfrac{1}{2}I_2)\right]\\ & = \mbox{Tr}\left[U^\dagger (\Lambda - \tfrac{1}{2}I_2)^\dagger UU^\dagger (\Lambda - \tfrac{1}{2}I_2) U\right]\\ & = \mbox{Tr}\left[(\Lambda - \tfrac{1}{2}I_2)^\dagger (\Lambda - \tfrac{1}{2}I_2) \right] = ||\Lambda - \tfrac{1}{2}I_2||^2. \end{align*}\]We can define distance between densities as the Hilbert-Schmidt norm times a positive constant $C$. We choose $C = \sqrt{2}$ so that for pure states with $p = 1$, the associated distance is $r = 2(p - 1/2) = 1$. In general, since each such $r$ is associated with a unique $\Lambda(p)$, we conclude that the space of $2\times 2$ density matrices is a ball consisting of concentric, transitive orbits of the unitary group, with the pure states at $p = 1$, the maximally mixed state at $p = 0$, and radius $r = 2(p - 1/2)$ for the orbit of $\Lambda(p)$.

Orbital mechanics

A similar story holds in higher dimensions. Density matrices are positive and unit trace, so each orbit in dimension $d$ has a canonical representative of the form

\[\Lambda = \mathrm{diag}(p_1, p_2, \ldots, p_d),\]where the positivity of $\rho$ and unit trace condition imply

\[\sum_{i=1}^d p_i = 1, \quad p_i \geq 0,\]and we can arrange eigenvalues in descending order:

\[p_1 \geq p_2 \geq \cdots \geq p_d \geq 0.\]The constraint that the eigenvalues sum to $1$ means that we only need $p_1, p_2, \ldots, p_{d-1}$ to uniquely specify a canonical representative $\Lambda(p_1, p_2, \ldots, p_{d-1})$. We can repeat the calculations from above to show that $I_d/d$ has a trivial orbit, and that any density matrix in the orbit of $\Lambda(p_1, \ldots, p_{d-1})$ has a fixed distance to the mixed state:

\[r^2(p_1, \ldots, p_{d-1}) = C_d\sum_{i=1}^d \left(p_i - \frac{1}{d}\right)^2,\]where we choose $C_d$ so that the pure states, with $p_1 = 1, p_2 = \cdots = p_d = 0$, have distance $r = 1$. For completeness, we note that

\[C_d = \frac{d^2}{d^2 - 2d + 2}.\]It’s a bit trickier to see what the orbits look like, but in the same way that $I_d$ is fixed by the group $\mathrm{U}(d)$, we can read off fixed subgroups from the eigenvalue decomposition. For instance, a pure state has

\[p_1 = 1, \quad p_2 = \cdots = p_d = 0.\]The first factor is fixed by $\mathrm{U}(1)$ (corresponding to global phase), while the last $d - 1$ factors are fixed by $\mathrm{U}(d-1)$. These act independently, so that the stabiliser of a pure state is $\mathrm{U}(1) \times \mathrm{U}(d-1)$. By the orbit-stabiliser theorem, the orbit of pure states has the (coset) structure

\[\frac{\mathrm{U}(d)}{\mathrm{U}(1) \times \mathrm{U}(d - 1)}.\]Since $\mathrm{U}(d)$ has dimension $d^2$, this pure space orbit has dimension

\[d^2 - 1^2 - (d - 1)^2 = 2d - 2,\]and lies on a unit sphere $\mathbb{S}^{2d-2}$ in our Hilbert-Schmidt metric. This agrees with the Bloch sphere for $d = 2$. This seems rather nice, but in general, the orbits will be horrible. First of all, spheres of radius $r < 1$ around the mixed state will now be made up of uncountably many orbits, since there are uncountably many sets of $p_i$ which solve

\[r^2 = C_d\sum_{i=1}^d \left(p_i -\frac{1}{d}\right)^2\]for $r < 1$. And orbits can be more elaborate for other eigenvalue structures. For instance, if we lump the $p_i$ into $k$ sets of distinct eigenvalues,

\[P_1, P_2, \ldots, P_K,\]with multiplicity $\mu_J$ associated to eigenvalue $P_J$, then the same argument as above shows that the coset structure is

\[\frac{\mathrm{U}(d)}{\mathrm{U}(\mu_1) \times \cdots \times \mathrm{U}(\mu_K)},\]known to mathematicians as a partial flag variety. These orbits have dimension

\[D = d^2 - \sum_{J=1}^K \mu_J^2,\]and lie on a sphere of radius

\[r^2 = C_d\sum_{J=1}^K \mu_J^2\left(P_J - \frac{1}{d}\right)^2.\]Note that while mixed states are closer to the maximally mixed state, unlike the Bloch ball, they do not lie inside the orbit of pure states. Typically, they have more dimensions! For instance, a generic point with no symmetries (distinct $p_i$), the cosets are of the form

\[\frac{\mathrm{U}(d)}{(\mathrm{U}(1))^d}\]with dimension $d^2 - d$, so for $d > 2$, these are always bigger than the pure state orbits. It’s certainly possible to say more about this, but who wants to. It’s a mess!

The simplicial wedge

Our modest goal will be to tidy up some of the mess. The main observation is that the eigenvalues $p_i$ form a probability distribution over $d$ outcomes. If they had an arbitrary order, they would live on the standard $(d-1)$-simplex $\Delta_{d-1}$, but because they are arranged in decreasing order, they live on the simplicial “wedge”:

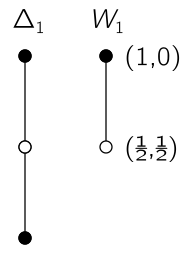

\[W_{d-1} = \left\{(p_1, \ldots, p_d) : \sum_{i=1}^d p_i = 1, p_1 \geq p_2 \geq \cdots \geq p_d \geq 0\right\}.\]Note that the subscript denotes the number of independent parameters. We can illustrate these ideas for $d = 2$:

We start with the $1$-simplex $\Delta_1$, and divide it two to get the wedge $W_1$. The black dot at the top is the orbit of pure states, and the white dot the maximally mixed state. In general, the wedge $W_{d-1}$ is almost a quotient of $\Delta_{d-1}$ by its symmetry group, the set of permutations $S_d$. But the wedge has literal “edge cases”, stabilised by subgroups of $S_d$ in a way that mirrors the corresponding unitary orbits. More precisely, if a point in $W_{d-1}$ is stabilised by $S_{\mu_1} \times \cdots \times S_{\mu_K}$, then the corresponding coset structure for the orbit is the partial flag variety

\[\frac{\mathrm{U}(d)}{\mathrm{U}(\mu_1) \times \cdots \times \mathrm{U}(\mu_K)}.\]For instance, pure states have canonical representative

\[(1, 0, 0, \ldots, 0) \in W_{d-1},\]which is stabilised by the subgroup $S_1 \times S_{d-1}$. This correctly gives the coset orbit

\[\frac{\mathrm{U}(d)}{\mathrm{U}(1) \times \mathrm{U}(d - 1)}.\]The maximally mixed state, and centroid of the whole simplex, has coordinates

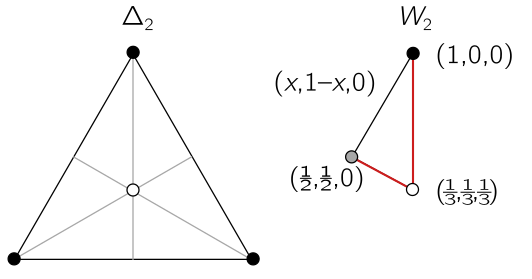

\[\frac{1}{d}(1, 1, \ldots, 1),\]and is stabilised by the full group $S_d$. As we expect, the orbit is trivial. We can see how this works for a qutrit below. We start with the $2$-simplex $\Delta_2$, an equilateral triangle, and cut out the wedge $W_2$:

At the top we have the pure states as usual, and the mixed state at the white centroid. The grey dot represents the fully mixed state on two basis elements. Note that, along the red edges, two coordinates agree, and in fact, each represents a copy of $W_1$, coinciding at the centroid. In general, orbit degeneracies occur precisely at sub-wedges $W_K$ with interiors parameterised by the coordinates $P_1, \ldots, P_K$ introduced above. But when distinct sub-wedge coincides, we get even more degeneracy. So, the apparent randomness of orbits is somewhat tamed by geometric hierarchy.

Finally, to relate this back to spheres, the nice thing about using the Frobenius norm is that the distance between a density matrix and the maximally mixed matrix is just proportional to the Euclidean distance on the wedge. So we can literally draw concentric spheres emanating from the centroid! Our scheme does not do away with all the messiness of the orbits. But it does provide a simple way to organise and read off some of their basic properties, and generalises in a reasonably natural way the concentric spheres of the Bloch ball.