Sums of squares and normed algebras

August 23, 2015. There are nice connections between representations of numbers as sums of squares, and the multiplicative structure of weird number systems. I explain some of these connections, and show why 3 × 21 = 63 tells us that a certain normed division algebra cannot exist!

Introduction

Prerequisites: second linear algebra course, some abstract algebra.

If $x$ and $y$ are both sums of perfect squares, so is their product $xy$. This follows from the algebraic identity

\[(a^2 + b^2)(c^2 + d^2) = (ac + bd)^2 + (ad-bc)^2.\tag{1}\]This is sometimes called the Brahmagupta–Fibonacci identity. Although it’s trivial, it helps us solve the classical problem of which positive integers can be represented as a sum of two squares, since we can break an integer into its prime factors and consider their representability. A similar identity holds for four squares:

\[\begin{align*} (a^2+b^2+c^2+d^2)(e^2+f^2+g^2+h^2) & = (ae - bf - cg - dh)^2 \\ & \quad+ (af + be + ch - gd)^2\\ & \quad+(ag - bh + ce + df)^2\\ & \quad+(ah + bg - cf + de)^2.\tag{2} \end{align*}\]This result can be used to show that any positive integer is a sum of at most four squares, since we can establish the corresponding result for all primes. Proving (1) and (2) is an exercise in high school algebra. But they turn out to represent something a bit deeper: the existence of a product-respecting norm for both the complex numbers and quaternions.

Normed algebras

Recall that an algebra is a vector space $\mathcal{A}$ over a field $\mathbb{F}$, along with a product $\cdot : \mathcal{A}\times \mathcal{A} \to \mathcal{A}$ which distributes over vector addition and commutes with scalar multiplication. More formally, for all $f \in \mathbb{F}$ and $x, y, z \in \mathcal{A}$,

\[\begin{align*} x(y + z) & = xy + xz, \\ (y + z)x & = yx + zx, \\ f(xy) &= (fx)y = x(fy). \end{align*}\]From now on we’ll assume that $\mathbb{F} = \mathbb{R}$. A multiplicative norm $|\cdot|$ on $\mathcal{A}$ is a measure of the size of elements in the algebra, $|x| \in \mathbb{R}_+$, which commutes with the product:

\[\begin{align*} |xy| & = |x||y|. \end{align*}\]If a multiplicative norm for $\mathcal{A}$ exists, it is said to be a normed algebra.

Silly high-tech proofs

Recall that the norm for $\mathbb{C}$ is multiplicative, and defined for $z = x+ iy$ by

\[|z| = |x + iy| = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2}.\]To establish identity (1), consider Gaussian integers $\alpha = a + bi$, $\beta = c + di \in \mathbb{C}$, $a, b, c, d \in \mathbb{Z}$. Then

\[\begin{align*} (a^2 + b^2)(c^2 + d^2) & = |\alpha|^2|\beta|^2 = |\alpha\beta|^2 \\ & = |(ac - bd) + (ad+bc)i|^2 \\ & = (ac-bd)^2+(ad+bc)^2. \end{align*}\]This is precisely formula (1). Let’s see how the analogous proof for (2) works. The quaternions $\mathbb{H}$ form a $4$-dimensional normed algebra. An element $\gamma \in \mathbb{H}$ can be written as a linear combination over the basis vectors ${1, i, j, k}$,

\[\gamma = x + yi + zj + wk\]for $x, y, z \in \mathbb{R}$. Here, as for $\mathbb{C}$, the vector labelled $1$ denotes the multiplicative unit,

\[1\cdot \gamma =\gamma\cdot 1 = \gamma\]for all $\gamma \in \mathbb{H}$. The vectors $i, j, k$ satisfy Hamilton’s identities (which, in a moment of famous mathematical vandalism, he carved onto a Dublin bridge),

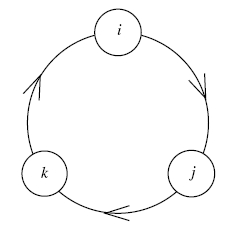

\[i^2 = j^2 = k^2 = -1, \quad ijk = -1.\]We can rewrite the second identity as $ij = k$, or $jk = i$, or $ki = j$. These last three rules are conveniently pictured using a diagram (from John Baez’s notes):

(We interpret a path $a \to b \to c$ as $ab = c$.) Thinking of $\mathbb{H}$ as $\mathbb{R}^4$ with some added multiplicative structure, the norm is the usual one, defined on $\mathbb{R}^4$ by

\[|\gamma|^2 = x^2 + y^2 + z^2 + w^2.\]Again, it turns out to be multiplicative. The proof of (2) then follows the same lines. Let $a+bi+cj+dk, e+fi+gj+hk \in \mathbb{H}$ be “Gaussian” quaternions. Then the product (using distributivity and the defining relations for $i, j, k$) is the “Gaussian” quaternion

\[\begin{align*} (a+bi+cj+dk)(e+fi+gj+hk) & = (ae - bf - cg - dh) + (af + be + ch - gd)i \\ & + (ag - bh + ce + df)j + (ah + bg - cf + de)k. \end{align*}\]Taking the norm of both sides and using multiplicativity gives (2). This time, I’ll leave the algebraic details to the interested reader!

The crazy uncle and Degen’s identity

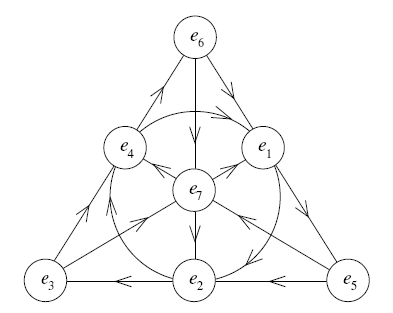

At this point, you may be wondering about the octonions $\mathbb{O}$, the “crazy uncle” of the family (in the colourful phrase of John Baez). This is an $8$-dimensional normed algebra with basis vectors labelled ${1, e_1, e_2, e_3, e_4, e_5, e_6, e_7}$ satisfying $e_i^2 = -1$ for $1 \leq i \leq 7$. The remaining rules are a bit tedious to write down, but thankfully there is a nice directed graph representation, as for the quaternions (again due to John Baez):

We read this as follows: to find $e_i\cdot e_j$, locate the line containing $e_i$ and $e_j$ on the diagram. Take that line, join the endpoints to form a $3$-cycle, and interpret products as for the quaternion diagram above. (This diagram may also be familiar as the Fano plane, a remarkable finite model of projective geometry.) You can verify that multiplication is no longer associative in the octonions. Any set of distinct generators will do!

Cutting to the chase, the octonion norm is defined in the expected way,

\[\left|\sum_{i=0}^7 a_i e_i\right| = \sqrt{\sum_{i=0}^7 a_i^2}\]where each $a_i \in \mathbb{R}$. As you would expect, multiplicativity gives an identity connecting expressing a product of sums of eight squares as a sum of eight squares. The identity was first discovered by Degen, roughly 30 years before octonions were invented. I won’t write it down: each of the eight squares contains eight binomial terms, so it’s rather long. But you could figure it out yourself if you have an afternoon to kill and a generous supply of paper.

Incidentally, you might be wondering how we show that the octonion (or, for that matter, the quaternion) norm is multiplicative without using the sums of squares identities. Basically, you can use something called the Cayley-Dickson construction to build the octonions from the quaternions, and the quaternions from the complex numbers, in a way that ensures multiplicativity holds.

The Hurwitz problem, $3\times 21 = 63$ and Pfister’s theorem

Returning to our original question about integers and sums of squares, is there a corresponding product identity for a sum of three squares? A simple example shows the answer is no. You can check by hand that both $3 = 1^2 + 1^2 + 1^2$ and $21 = 1^2 + 2^2 + 4^2$ can be written as a sum of three perfect squares but no fewer. On the other hand, $63 = 3\times 21$ cannot be written as a sum of fewer than four perfect squares. Hence, no simple algebraic identity (with integer coefficients as above) can hold for three squares.

More generally, the existence of these sum-of-squares identities, where the terms on the right are bilinear in the terms on the left, is called the Hurwitz problem. We’ve been discussed the classical Hurwitz problem over $\mathbb{R}$. Hurwitz solved this in 1898, showing that bilinear expressions only exist for sums of $d$ squares, where $d = 1, 2, 4, 8$. Exploiting the connection between these identities and multiplicative norms, this result can be turned around to show that normed algebras only exist for dimension $d = 1, 2, 4, 8$! An example of an algebra in each dimension is given by $\mathbb{R}$, $\mathbb{C}$, $\mathbb{H}$ and $\mathbb{O}$ respectively, though others exist. I think it’s a great example of the power of mathematical thinking that $3\times 21=63$ is a big step towards proving the non-existence of normed algebras for $d = 3$!

You might be wondering about the pattern of binary powers in these dimensions. This is related to the Cayley-Dickson construction I mentioned earlier, and applying it to the octonions gives a $16$-dimensional structure called the sedenions $\mathbb{S}$. This is not a normed algebra, but there is a corresponding non-bilinear sixteen-square identity due to Zazzenhaus and Eichhorn, and independently Pfister, in the 60s. In fact, Pfister proved the more general result that non-bilinear sums of squares identities exist for all binary $d = 2^n$. I suspect this can be related to the Cayley-Dickson construction (though I haven’t looked into it). Keith Conrad has a nice article discussing Pfister’s general result, which I might talk about another time.

References

- Number Theory (1971), George Andrews.

- The Octonions, John Baez.

- “Pfister’s theorem on sums of squares”, Keith Conrad.