Integrals from pyramids

January 22, 2021. I present an elementary, first-principles trick for integrating polynomials: splitting a hypercube into congruent pyramids.

Introduction

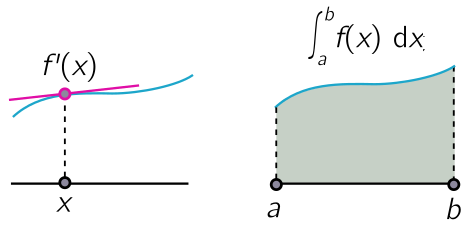

Derivatives compute slopes at a point. Integrals compute areas under curves. The first is a local operation, involving only information in a neighbourhood of a point, while the latter is global, involving the value of the function at different points. This makes integration a lot harder than differentiation!

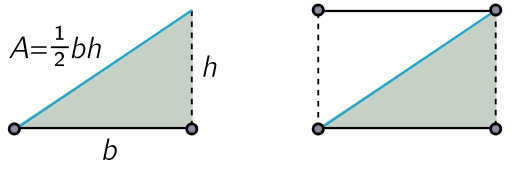

However, sometimes we have a shortcut for integrating: identifying an integral with the volume of a solid. A simple example is a linear function, $f(x) = mx$. When we integrate from $x = 0$ to $x = b$, the area under the curve is just a triangle, obeying $A = bh/2$ for height $h = mb$. We can represent this reasoning in a picture:

But what happens if we want to integrate $x^2$? There doesn’t seem to be any analogous geometry, and we are forced to do something fancy (like use the fundamental theorem of calculus) if we want to find the area under the curve.

A triangular warm-up

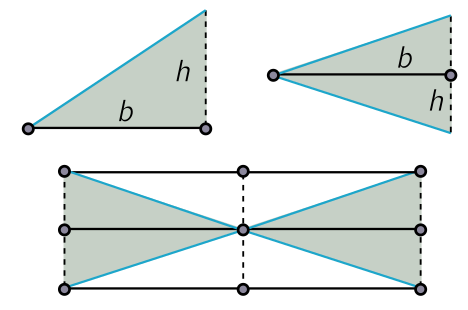

But it turns out we haven’t tried hard enough! There is a simple geometric approach to integrating $x^2$ and all the higher monomials $x^n$. This lets us integrate any polynomial by simply adding monomial terms. To see how to do this, let’s first think of the integral of a linear function in a slightly different way. Rather than as half a square, let’s slide the “height” of the triangle down so it becomes isosceles. The area is unchanged since $b$ and $h$ have now swapped roles.

Now we double this triangle, and see it covers half of a square of area $2bh$. Since twice the area of the triangle equals half the area of this square,

\[2A = \frac{1}{2} \cdot 2bh \quad \Longrightarrow \quad A = \frac{1}{2}bh.\]This may seem like a convoluted reinterpretation, but it generalises in a lovely way to help us integrate polynomials.

Pyramids and hypercubes

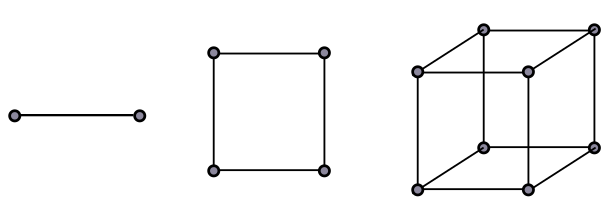

A hypercube or $n$-cube is a cube in $n$ dimensions. Formally, we can view it as all points

\[I^n = \{(x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n) : x_i \in [0, 1]\} = [0, 1]^n.\]For instance, a $1$-cube is the unit interval $I = [0, 1]$, while a $2$-cube is the unit square $[0 ,1]^2$. The $3$-cube is what we usually mean by a “cube”. Now, the length of the unit interval is $1$, the area of the unit square is $1^1 = 1$, and volume of the unit cube is $1^3 = 1$. The pattern continues, with the volume simply given by the product of the length of each side of the hypercube, $1^n = 1$.

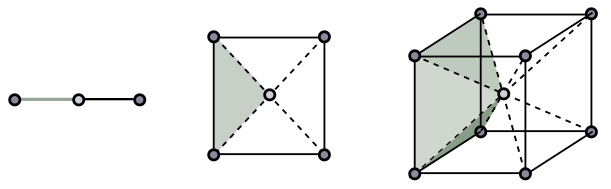

Let us now divide a hypercube in the following way: draw a point at the centre, and from that point, draw a line to each corner. These lines form the edges of a $(n-1)$-hypercube-based hyperpyramid, which sounds a bit crazy but is actually very simple. We illustrate for the simple cases below.

Each of these (hyper)pyramids is congruent, i.e. has the same shape, so to work out their volume, all we need to do is compute how many there are. Since each pyramid has a $(n-1)$-cube or face as a base, this is the same as counting faces. But this is easy: along any dimension there are two faces, corresponding to fixing $x_i = 0$ or $x_i = 1$ for some $i$. Thus, there are $2n$ faces. Just to check this makes sense, we have $2 \cdot 1 = 2$ “faces” or endpoints for a line, $2 \cdot 2 = 4$ sides to a square, and $2 \cdot 3 = 6$ faces for a cube. Thus, each pyramid has a volume

\[V_n = \frac{1}{2n}.\]To connect to our warm-up exercise, note that in two dimensions, the pyramid is a triangle with a side as its base.

Slicing pyramids

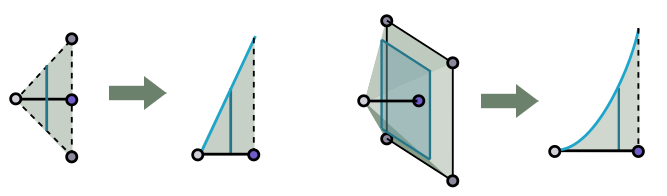

Let’s now focus on a single pyramid. We can move along the line from the tip to the centre of the base, and graph the area of the cross-section of pyramid passing through that point, parallel to the base. Each slice will be a shrunken copy of the base itself. As examples, on the square the “pyramid” is just a quarter triangle. The cross-section is a line (a copy of the base, which is a side of the square), which is increasing linearly in length. Similarly, for a cube, the pyramid is a bonafide square-based pyramid, and each slice is a square as well. We draw some pictures below:

As we go along, the side length of the slice will change linearly. But the area will change in a way that depends on the dimension we are working in! It stays linear on the square, since it has $2 - 1 = 1$ dimension. For a cube with $n = 3$, the slice is a square whose area changes quadratically. The pattern continues, and in $n$ dimensions, slicing a pyramid results in a cross-section which grows as $x^{n-1}$ for a parameter $x$ going from $x = 0$ at the tip of the pyramid to $x = 1$ at the base.

Integrating monomials

We can add up the area of each cross-section precisely by integrating with respect to $x$. The answer is not quite the volume of the pyramid, however, since the distance from the tip of the pyramid to the centre of the base is actually $d = 1/2$. So $x$ is twice the actual distance. If we want to integrate to find the volume, the correct “infinitesimal width” of a cross-section is not $dx$, but $dx/2$. The corresponding integral should then give us the volume we calculated above:

\[\int_0^{1} x^{n-1} \, \frac{dx}{2} = V_n = \frac{1}{2n} \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \int_0^{1} x^{n-1} \, dx = \frac{1}{n}.\]If instead of a unit hypercube, we have a cube of side length $b$, then the volume of the whole hypercube is $b^n$, and hence the volume of a pyramid is $b^n/2n$. If we let our parameter $x$ go from $x = 0$ at the tip to $x = b$ at the base, then once again it is twice the distance, and the same reasoning shows that

\[\int_0^{b} x^{n-1} \, dx = \frac{b^n}{n}.\]Thus, we have geometrically integrated an arbitrary monomial!

Acknowledgments

Thanks to J.A. for a stimulating discussion of integration from first principles.