Asymmetric dice are unfair

November 3, 2020. Symmetric dice are fair since you cannot tell faces apart. This obviates the need to consider the mechanics of rolling. Here, I analyse the mechanics of asymmetric, two-dimensional dice and show they can always be “dynamically loaded”, i.e. loaded by rolling at different speeds. So fairness implies symmetry!

Introduction

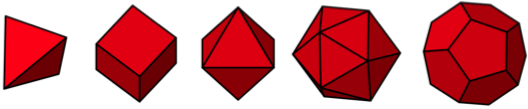

If a dice is made of homogenous material, it’s easy to ensure it’s fair: simply pick a shape where the sides are indistinguishable, or in technical language, isohedral. Then it is as likely to land on one side as any other, since you have no way of telling them apart if you remove the numbers. The simplest example is the Platonic solids, where not only the faces but the vertices are indistinguishable. These have 4 (tetrahedron), 6 (cube), 8 (octahedron), 12 (icosahedron) and 20 (dodecahedron) sides. There is a more general class of a isohedral shapes which are not symmetric between vertices, called the Catalan solids, but I won’t describe them here.

It’s clear that, however you roll the dice, as long as the impact parameter is random, the probability distribution should be uniform. There is no way to bias towards a face if all the faces are the same. But what if the faces are different? In this case, as we will see, the probability distribution depends on how you roll. This leads to a notion of “dynamic loading”: a dice which is fair in some regime can be loaded by rolling it differently. We therefore learn that not only does symmetry imply fairness, but the converse holds as well, at least in the simple setup we will consider.

Dice in two dimensions

We’re going to focus on the tractable case of a two-dimensional dice. We will ignore its translational motion, the additional complications of frictions, etc, and focus on the key mechanism of the roll: angular momentum. In more detail, suppose we have a convex polygon of $n$ sides. It has some varying density, but because it is convex, the centre of mass $C$ is inside the polygon somewhere. Hopefully this is intuitive; to get it to fall outside the shape, one needs some non-convex “wings” which spread out.

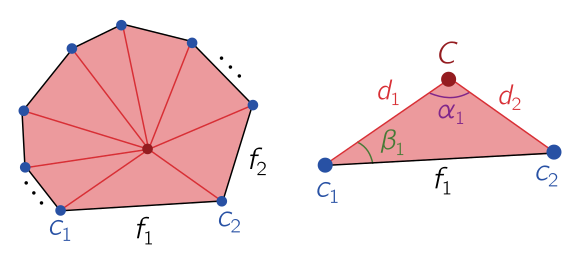

We will need some further parameters. Let us label the corners $c_i$ and faces $f_i$ anticlockwise, $i = 1, \ldots, n$, with $f_i$ between $c_i$ and $c_{i+1}$. Each corner is a distance $d_i$ from the centre of mass, and each face subtends a face angle $\alpha_i$, as well as a left corner angle $\beta_i$, defined in the figure.

When the dice is rolled, the roller imparts some angular momentum $L = \omega I$ around the centre of mass, where $I$ is the moment of inertia and $\omega$ the angular velocity. We will assume that when the dice falls, it lands at some random, uniformly chosen angle around $C$. It will almost certainly land on a corner, and then roll one or more times so it sits on a face. We are going to ignore linear motion, and focus only on the effects of angular momentum on the probability distribution. Finally, we assume that the result of the throw is that face it lands on.

In order to ensure it can land on all faces, we assume that the centre of mass lies above all the faces when they lay flush with the surface. Put differently, none of the triangles $\triangle Cc_{i}c_{i+1}$ are oblique. We call such a dice acute.

Slow fairness

To begin with, let’s suppose that $\omega = 0$. The dice simply falls down at some random, uniformly chosen angle around the centre of mass, and tilts over to lie on the closest side. If the angle falls within the angle $\alpha_i$ subtended by face $f_i$, it will fall onto this face. Thus, the probability of obtaining the face is

\[p_i^\text{slow} = \frac{\alpha_i}{2\pi}.\]The probabilities $p_i^\text{slow}$ remain a good approximation to the probability distribution when the dice are rolled very slowly (we will explain how slow below), so the chance of tipping over due to angular momentum is low.

We say that a dice obey slow fairness if this distribution is uniform:

\[\alpha_i = \frac{2\pi}{n}.\]The faces of a slowly fair dice subtend equal angles. Incidentally, this does not mean faces have the same areas! But a comparatively large face, subtending the same angle, means the centre of mass is closer to the short sides. The smaller area is compensated for by the concentration of mass.

The flip barrier

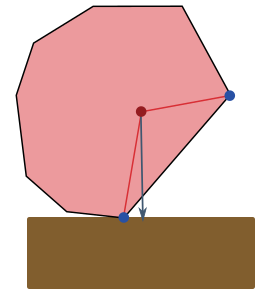

Let’s now consider nonzero $\omega$. In particular, we can analyse how much energy it takes to flip the dice from face $f_i$ to $f_{i-1}$, supposing it rolls clockwise. The centre of mass sits at a height

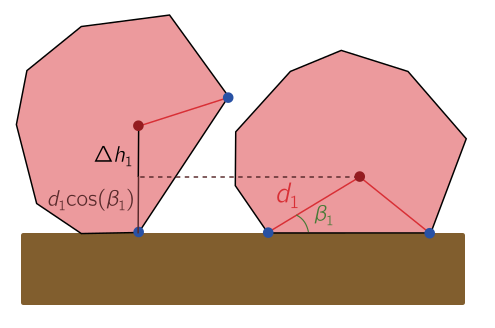

\[h_i = d_i \cos \beta_i.\]In order to roll over to $f_{i-1}$, it needs to be raised to a height $d_i$, so the dice is standing on the corner with the line from $C$ to $c_i$ vertical. (Note that this assumes the dice is acute; otherwise, it may not be possible for the line from $C$ to $c_i$ to be vertical while the dice is standing on $c_i$.) The height difference is then

\[\Delta h_i = d_i(1 - \cos\beta_i).\]We draw a picture below:

If the dice has mass $m$, the corresponding change in gravitational potential energy or flip barrier $B_i$ is

\[B_i = mg \Delta h_i = mg d_i(1 - \cos\beta_i).\]This energy will be supplied in the form of rotational kinetic energy by the roller. If the dice has kinetic energy $K = I\omega^2/2$, it will be able to flip to the next face provided $K > B_i$. Incidentally, this tells when our first approximation is good: when the kinetic energy $K \ll \min_i B_i$.

Dynamic loading and fairness

The flip barrier shows that dice can be dynamically loaded, i.e. that the probability distribution will depend on the speed of rolling. The argument is simple. The dice is rolled clockwise with some energy $K$ and lands at corner $c_{i+1}$. Whether it continues rolling depends on whether it can overcome the flip barrier, which will clearly depend on how much rotational kinetic energy it has to begin with.

There is some fine print. The first flip can take or remove energy, and determining the probabilities involved is intricate. I will ignore these! This is somewhat justified by the fact that if the dice obeys slow fairness, with the angular size of each face the same, the effects of the first roll should be approximately independent of which corner you hit. Similarly, it is clear that friction plays an important role in making the dice stop; otherwise, a dice with enough kinetic energy will overcome all flip barriers and keep rolling forever. Assuming the surface has high static friction so there is no sliding, friction is not relevant to these symmetry arguments, so I will ignore it.

Whatever the complexities of the first flip, the argument for dynamic loading fails when the flip barrier is uniform, and hence

\[\Delta h_i = d_i(1 - \cos\beta_i)\]is the same for all faces. If we also assume static fairness, $\alpha_i = 2\pi/n$, we find that the right-corner angle $\gamma_i$ must obey

\[\beta_i + \gamma_i = \pi - \frac{2\pi}{n},\]since the angles add up to $\pi$. The law of sines implies

\[\frac{d_{i+1}}{\beta_i} = \frac{d_{i}}{\gamma_i} \quad \Longrightarrow \quad d_{i+1} = d_i \left(\frac{\beta_i}{\pi - \frac{2\pi}{n} - \beta_i}\right).\]Then our condition that $\Delta h_i$ is constant gives

\[(1- \cos\beta_i) = \left(\frac{\beta_i}{\pi - \frac{2\pi}{n} - \beta_i}\right) (1-\cos\beta_{i+1}).\]Iterating $n$ times around the whole polygon, we find that

\[\left(\frac{\beta_i}{\pi - \frac{2\pi}{n} - \beta_i}\right)^n = 1 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \beta_i = \pi - \frac{2\pi}{n} - \beta_i\]and hence $\beta_i = \gamma_i = \pi(2^{-1} - n^{-1})$. Each triangle is similar. Then constancy of $\Delta h_i$ then implies the $d_i$ are uniform, so the triangles are not only similar, but congruent, and arrayed to form a regular polygon, with the centre of mass at the point of rotational symmetry. Taking the contrapositive, we learn that asymmetric dice must be unfair. They can always be dynamically loaded.

Higher dimensions

I’ve only been talking about two-dimensional dice. Does this result hold in higher dimensions? I think it should. Instead of choosing a random angle, we choose a random point on the sphere (or hypersphere!) to set down the dice, uniform with respect to the centre of mass. Assuming it is acute, so that the centre of mass is above a face when it sits flat on the surface, the slow fairness argument can be repeated to show that any face must subtend the same solid angle.

Adjacent faces will be separated by a flip barrier. I’m not sure how to generalize the two-dimensional argument, but it seems likely that slowly fair dice with uniform flip barriers are regular, or at least isohedral. I’ll leave this argument for another post. But even in the two-dimensional case, it’s nice to see symmetry emerge from fairness, rather than the other way round!