Turning a thermometer into a sundial

January 28, 2021. I attempt to turn a thermometer (or more specifically, data about the maximum daily temperature) into a sundial. Though it fails on earth, it works on Mercury!

Introduction

The sun heats the earth up, and the earth radiates that heat back into space. As the sun sets, less heat is delivered, and the maximum temperature occurs when the two rates—heat delivered and heat radiated—balance. In this post, we’ll work out how this simple requirement relates maximum temperature to the latitude, time of year, and time of day the maximum occurs, meaning that a thermometer can in principle be used as a sort of sundial. In practice, this is only the first step towards a realistic model, but for the purpose of building narrative tension, I will let the shortcomings of my approach unfold naturally.

Energy balance

Consider a small patch of the earth’s surface of unit area, at the point it attains its maximum temperature $T_\text{max}$ in Kelvin. According to the Stefan-Boltzmann law, it radiates energy away with intensity

\[I_\text{out} = \sigma T_\text{max}^4, \quad \sigma = 5.67 \times 10^{-8} \frac{\text{W}}{\text{m}^2 \text{ K}}.\]Since this is the maximum attained, it must equal the intensity of incoming solar radiation $I_\text{in}$. To a good approximation, this is the radiant intensity of sunlight striking the earth’s surface head on, the so-called insolation constant $I_0$, multiplied by a geometric term $\cos^2\vartheta$ (where $\vartheta$ is the angle the sunlight makes with the vertical to the ground), and an albedo term $(1-a)$ to account for sunlight reflected back:

\[I_\text{in} = I_0 (1- a )\cos^2\vartheta.\]The insolation constant is $I_0 = 1367 \text{ W/m}^2$ [1]. The albedo of the earth is around $a = 0.3$, i.e. $30\%$ reflected back into space on average, though this depends on cloud cover, snow, and so on. We will talk about $\vartheta$ more in a moment. Setting $I_\text{in} = I_\text{out}$ when the maximum is obtained, we find

\[I_0 (1- a )\cos^2\vartheta = \sigma T_\text{max}^4. \label{balance} \tag{1}\]Thus, the maximum temperature is directly related to the length of shadow!

Geometry and heliometry

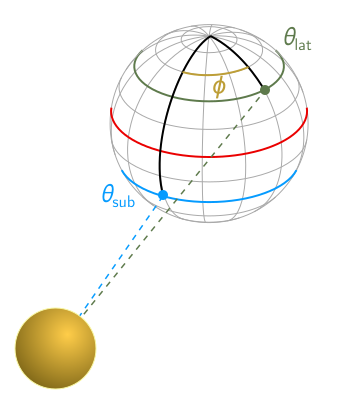

Even more interesting is how $\vartheta$ is related to the earth-sun geometry, and the parameters of latitude, time of year, and time of day. The point directly below the sun, called the subsolar point, rotates at some line of latitude around the earth, with azimuthal angle $\theta_\text{sub}$, depending on the time of year. Here is a basic picture of the setup:

At either equinox, it coincides with the equator (red line). At the (northern hemisphere’s) summer solstice, it runs along the Tropic of Cancer, about $23.5^\circ$ north of the equator. At the winter solstice, it lies $23.5^\circ$ south of the equator, on the Tropic of Capricorn. If we draw the orbit of the earth as a circle around the sun, with $\varphi = 0$ at the winter solstice and increasing with time, then the subsolar latitude, measured in radians from the north pole, roughly obeys

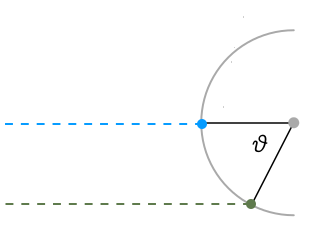

\[\theta_\text{sub} = \frac{\pi}{2} + \left(\frac{2\pi}{360}\right) 23.5 \cos(\varphi). \label{year} \tag{2}\]To calculate the angle $\vartheta$, we need two additional data points: the latitude of the observation point (measured from north pole) and the polar angle $\phi$ between the observation point and the current subsolar point. This simply measures time from solar noon. To determine $\vartheta$, first note that if we draw the subsolar and observation point on the same great circle of the earth, $\vartheta$ is clearly the angle between the black lines, drawn from each point to the centre of the earth [2]:

This means we can easily determine $\cos\vartheta$ using vectors, simply by taking the dot product. To begin with, we write in spherical coordinates $(\theta,\phi)$, then convert to Cartesian coordinates $(x, y, z)$:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{x}_\text{sub} (\theta_{\text{sub}}, 0) & = (\sin \theta_\text{sub}, 0, \cos\theta_\text{sub}) \\ \mathbf{x}_\text{obs} (\theta_{\text{lat}}, \phi) & = (\sin \theta_\text{lat}\cos\phi, \sin \theta_\text{lat}\sin\phi, \cos \theta_\text{lat}). \end{align*}\]We can immediately determine the dot product:

\[\cos\vartheta = \mathbf{x}_\text{sub} \cdot \mathbf{x}_\text{obs} = \cos\theta_\text{sub}\cos\theta_\text{lat} + \sin \theta_\text{sub}\sin \theta_\text{lat}\cos \phi. \label{geohelio} \tag{3}\]Plugging this back into (\ref{balance}), we find a relationship between maximum temperature $T_\text{max}$, time of year via $\theta_\text{sub}$, latitude $\theta_\text{lat}$, and time of day, or rather, time past solar noon $\phi$.

Real data

The question is: how does this stack up against real data? I’ll take some local weather data. In Vancouver, the latitude is $49.3^\circ$ north of the equator, with azimuthal coordinate

\[\theta_{\text{lat}} = \left(\frac{2\pi}{360}\right)(90 - 49.3) \approx 0.71.\]It’s $36$ days or about tenth of a year since the winter solstice, so from (\ref{year}), the subsolar latitude is

\[\theta_\text{sub} = \frac{\pi}{2} + \left(\frac{2\pi }{360}\right) 23.5 \cos(0.1 \cdot 2\pi) \approx 1.9.\]This agrees with real-time data on the subsolar point. Finally, the maximum temperature yesterday was $7^\circ \text{ C} = 280 \text{ K}$, and cloud cover makes $a \approx 0.35$. Thus, rearranging (\ref{geohelio}) and (\ref{balance}), we expect the maximum to occur at a “time of day angle” $\phi$ given by

\[\begin{align*} \cos \phi & = \frac{\sqrt{\frac{\sigma T_\text{max}^4}{I_0(1-a)}} - \cos\theta_\text{sub}\cos\theta_\text{lat}}{\sin \theta_\text{sub}\sin \theta_\text{lat}} \\ & = \frac{\sqrt{\frac{(5.67 \times 10^{-8}) 280^4}{1367(1-0.3)}} - \cos 1.9\cos 0.71}{\sin 1.9\sin 0.71} \\ & \approx 1.37. \end{align*}\]Hopefully the problem is clear. The last term is bigger than one, and cannot possibly be equal the first term! If we plug in the time it peaked, a few hours after solar noon, we can rearrange and solve to find a predicted maximum temperature of $-80^\circ \text{ C}$! So something is very wrong.

Conclusion

We’ve neglected an important factor: the atmosphere. This is the very same thing needed to explain why the temperature of the earth is higher than expected from a simple energy balance argument. Basically, the atmosphere acts as a heat bath in contact with the earth, allowing for greater maximal temperatures. It may be possible to turn a thermometer into an accurate sundial using a simple greenhouse model. However, with parameters appropriately modified, our naive approach should work on a planet without substantial atmosphere like Mercury.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to A.B. for asking when daily temperatures peak, and suggesting this might depend on latitude.

This comes once more from the Stefan-Boltzmann law (for the surface temperature of the sun $T_\odot = 5800 \text{ K}$), and an inverse square drop-off: $$ I_0 = \sigma T_\odot^4 \left(\frac{R_\odot}{d}\right)^2 = 5.67 \times 10^{-8} \cdot 5800^4 \left(\frac{7 \times 10^5}{1.5\times 10^8}\right)^2\, \frac{\text{W}}{\text{m}^2}\approx 1400 \, \frac{\text{W}}{\text{m}^2}, $$ where $R_\odot = 7 \times 10^5 \text{ km}$ is the solar radius and $d = 1.5 \times 10^8 \text{ km}$ the earth-sun distance.

We are making the usual assumption that the sun is far enough away to treat incoming rays as parallel. For the same reason, we ignore the way radiant intensity changes (due to the inverse square law) with $\vartheta$.