Incompleteness and provability logic

December 14, 2017. Studying Gödel’s theorems in their original arithmetic context involves a lot of detail and hard work if all you are interested in is the logical content (e.g. Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems). I talk about an alternative called provability logic, which cleanly extracts all the interesting logical behaviour. In this context, Gödel’s results reduce to a single logical axiom called Löb’s Theorem and the existence of certain propositional fixed points.

Introduction

Prerequisites: propositional logic, some exposure to modal logic.

Gödel’s famous First Incompleteness Theorem hinges on the fact that a sufficiently expressive formal system (like ordinary arithmetic) can be jerry-rigged to make statements which are true but not provable. The basic idea: give statements labels so you can refer to them, and a way of talking about provability. Then combine them to make a sentence which says

I am not provable.

More accurately, we would construct a sentence L (for “liar”) which says

Statement L is not provable.

If the formal system is consistent — it can’t prove false statements — then it cannot prove L, since if L was provable, the sentence would be false. This means L must be true! A formal system which cannot prove all the statements about it that are true is called incomplete. So, the First Incompleteness Theorem just states that consistent systems which can refer to themselves, and make statements about provability, must be incomplete.

|

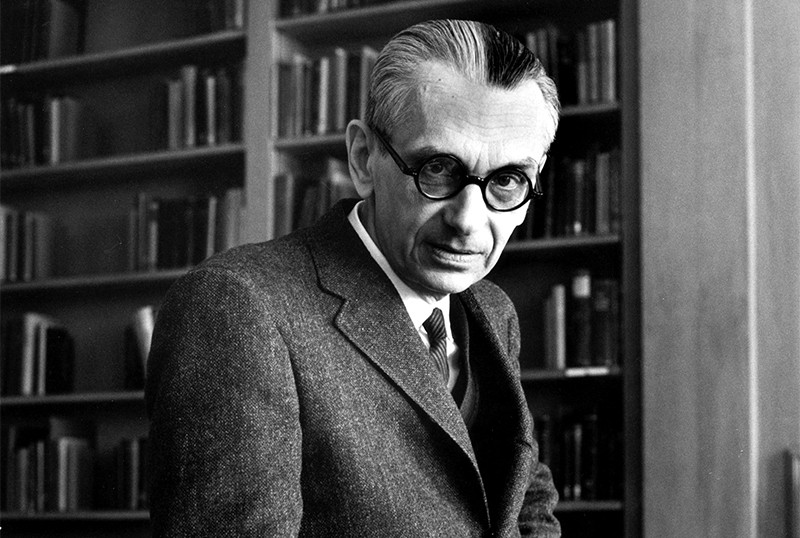

| Kurt Gödel (aka The Dark Lord). Alfred Eisenstaedt, Time Life Pictures. |

The Second Incompleteness Theorem is a sort of converse. It turns out that if a system can prove it is consistent, then this must be false: the system will be inconsistent! So, there is a statement in the system which is false but provable, as opposed to true but unprovable. To move beyond these high-concept summaries, usually one takes a course in mathematical logic and learns how to do elaborate and terrible things to basic arithmetic. But if you all you care about is the logical properties of provability, there is an easier way!

Expressing provability

Enter modal logic, a type of philosophical logic designed to handle possibility, necessity, and other modal notions of natural language. More recently, it was discovered that modal logic is perfectly adapted to treat provability, giving a clean and elegant characterisation of Gödel’s Theorems, and deeper insights into provability in formal systems. The goal of this post to explain how. I’m going to assume you know propositional logic and a little modal logic, though we won’t need much of the latter.

First, we need some way of expressing the provability of a statement. If $p$ is a statement, e.g. $``1 + 1 = 2”$, then let $\square p$ be the statement “$p$ is provable”. We call $\square$ the provability predicate, since it acts like an adjective applied to the sentence $p$. More formally, it is an operator which takes a proposition and returns a proposition, or a propositional operator. Now, we could be thinking about provability in a particular formal system, like Peano arithmetic. I will explain what this is below. But the nice thing about logic is that it frees us from the messy details of any particular system and lets us focus on deductive relations instead.

For the time being, we just fix a formal system $F$, with some semantics (a notion of what statements are true in the system) and a syntax (a way of proving statements in the system). If $p$ is true (from the semantics), we write $F \models p$. If we can prove $p$ (from the syntax), we write $F \vdash p$. (We usually omit $F$.) We call $F$ sound if $F \vdash p$ implies $F \models p$, and complete if $F \models p$ implies $F \vdash p$. Gödel’s theorems show that $\vdash p$, $\vdash\square p$ and $\models \square p$ are distinct but related in interesting ways!

To illustrate, suppose I want to say that $F$ is inconsistent. By definition, that means that $F$ can prove something false. We let $\bot$ denote falsum, a logical constant which always evaluates to false; if you prefer, choose a particular contradiction, e.g. $\bot = p \wedge \neg p$. (Its partner is the constant true, or verum, $\top$.) So $F$ is inconsistent iff we can prove a falsehood,

\[\square \bot.\]Now we can easily state Gödel’s Theorems. The First Theorem means that, for some statement $p$, we have $\models p \wedge \neg\square p$, i.e. $p$ is true but not provable. The second says

\[\square \neg \square \bot \to \square \bot.\]If you can prove you’re consistent, you must be lying!

Löb’s Theorem

So far, all we’ve done is introduce some symbols. We haven’t yet defined a logic, that is, a set of basic formulas (axioms), and rules of inference for generating new formulas from old. Amazingly, almost all the logical behaviour of provability (in a system like Peano arithmetic) can be captured by a single axiom, due to Martin Löb:

\[\square(\square A \to A) \to \square A. \tag{GL}\]This is called Löb’s Theorem, or $\mathbf{GL}$ (for Gödel-Löb). Here is an English gloss: if you can prove that proving $A$ makes it true, then you can prove $A$. Note that “proving $A$ makes it true” is a sort of local soundness condition, so Löb’s theorem says that if you can prove local soundness for $A$, you can prove $A$. We will motivative this axiom shortly, but to complete the description of provability logic, we add another axiom called $\mathbf{K}$ (for Kripke),

\[\square(A \to B) \to (\square A \to \square B). \tag{K}\]Here, $A$ and $B$ are understood to stand for any logical formulas. This is a sensible property for a provability predicate $\square$: if I can prove $A$ implies $B$, and I can prove $A$, then I should be able to string them together using modus ponens to get a proof of $B$. We also add all classical (propositional) tautologies as axioms, though we are allowed to replace propositional variables with arbitrary modal formulas. Finally, our rules of inference (for making new theorems from axioms) are necessitation and modus ponens:

\[\begin{align} A \quad &\implies \quad \square A \tag{N}\\ A, A \to B \quad &\implies \quad B. \tag{MP} \end{align}\]That’s it! We’ll discuss how these properties map onto “real life” formal systems of interest shortly. But in a fairly comprehensive sense, the behaviour of PA is captured by provability logic.

Exercise 1. Löb implies Gödel. Show that Löb’s Theorem implies Gödel’s Second Theorem. (Kripke showed that the converse also holds in PA.)

Peano Arithmetic and arithmetic completeness

Peano arithmetic (PA) is a simple formal system for dealing with natural numbers. I’m not going to describe it in any great detail; basically, you start with $0$ and a successor function $s$ which just adds $1$ to any number, so that

\[1 = s0, \quad 2 = s1 = ss0, \quad 3 = s2 = sss0 \ldots\]You can capture the properties of addition, multiplication, and mathematical induction using axioms. Gödel set up an ingenious labelling system (now called Gödel numbering) which allows numbers to refer to statements in PA; the powers in the prime factorisation correspond to symbols in a string. The Gödel number of a statement is usually denoted by corner brackets, $\ulcorner p\urcorner$. By including corner brackets, numbers, and logical symbols in your Gödel numbering system, you can start performing self-reference and talking about provability: the basic ingredients for incompleteness!

We won’t concern ourselves with the details here, since provability logic lets us abstract from these convoluted (if beautiful) details. But how do we know this abstraction works? And what is the relation between provability logic and PA? To answer both questiosn, we consider embedding functions $*: \mathcal{L}_0 \to \text{PA}$ which map the propositional variables $\mathcal{L}_0 = {p_1, p_2, \ldots }$ to statements in PA, and recurse on more complicated sentences, i.e.

\[*(\square A) = \square (*A), \quad *(\neg A) = \neg (*A), \quad *(A \to B) = *A \to *B.\]There are uncountably many such embedding functions. A sentence $A$ of provability logic is always provable if $* A$ is a theorem of PA for any embedding $* $. Provability logic is sound with respect to the semantics of PA if every theorem of provability logic is always provable. This, it turns out, isn’t too hard to show (for details see Boolos).

Arithmetic Completeness is the much less trivial assertion that every modal sentence which is always provable is a theorem of provability logic. In other words, any provable statement you make about provability in PA, within PA itself, is mapped onto a corresponding statement in provability logic. This was demonstrated by Solovay in 1976. It is essential; without it, provability logic might only capture of fragment of the provability behaviour of PA, but as it turns out, all you need is Löb.

Fixed points and truthers

We’ve seen that Gödel’s Second Theorem follows immediately from Löb’s theorem. How does Gödel’s First Theorem fit into the picture? To see this, we need to revisit the notion of self-reference but in a logical context. Consider a propositional predicate $P(x)$, i.e. an expression with a “hole” in it for a sentence $x$. An example is $L(x) = \neg \square x$. A fixed point of $P(x)$ is a formula $A$ satisfying $\models A \leftrightarrow P(A)$. This is analogous to the definition of a fixed point in mathematics, where instead of logical equivalence we have equality, $f(x) = x$. Gödel’s First Theorem is just the assertion of the existence of a fixed point for $L(x) = \neg \square x$:

\[A \leftrightarrow \neg \square A.\]Carnap observed that, in formal systems like PA which can be made to speak about themselves, all predicates have a fixed point. This is also called the diagonal lemma, since (as Raatikainen’s simple proof shows) the fixed point of $P(x)$ is obtained by applying a related predicate to itself, in a way reminiscent of Cantor’s diagonal argument. At any rate, the diagonal lemma for PA implies $L(x)$ has a fixed point, and hence Gödel’s First Theorem.

Before addressing how these fixed points arise in provability logic, let’s quickly look at another predicate, $T(x) = \square x$. A fixed point here is the opposite of a liar sentence: this sentence asserts its own provability. From Carnap’s observation, such sentences exist in PA, and in the 1950s, Leon Henkin asked whether these “truthers” were always provable or not. Löb showed that, in PA and related systems, these fixed points are always provable. This is the property of provability captured by Löb’s Theorem!

Let’s return to the main thread. Since provability logic has no Gödel numbers or other means of self-reference, we need to get at the fixed points a different way. A remarkably powerful tool is provided by the Fixed Point Theorem of de Jongh and Sambin. To state it, we need a little more terminology. A sentence $A$ is modalised in a propositional variable if that variable always occurs within the scope of $\square$, e.g. $\square \square p$, $\neg \square p \wedge q$ are modalised in $p$, but $p \vee \neg \square p$ is not. The Fixed Point Theorem states, if $A(p)$ is modalised in $p$, then there is a sentence $H$ not involving $p$, such that the following is a theorem of provability logic:

\[\square (p \leftrightarrow A(p)) \leftrightarrow \square (p \leftrightarrow H).\]This looks complicated, but it basically says that $H$ is logically equivalent to a fixed point of $A(x)$. More precisely, we can look at the statements in PA; since PA is sound, for any realisation we have

\[\text{PA} \vdash *p \leftrightarrow *A(p) \quad \text{iff} \quad \text{PA} \vdash *p \leftrightarrow *H.\]The theorem is also constructive, providing an algorithm for building $H$ from $A(p)$. Some examples:

\[\begin{align} A_1=\square p &\implies H_1=\top\\ A_2=\neg \square p &\implies H_2=\neg \square \bot \\ A_3=\square \neg p &\implies H_3=\square \bot \\ A_4=\neg \square \neg p &\implies H_4=\bot. \end{align}\]So, for instance, a fixed point of $L(x)$ (or $A_2$) is equivalent to $\neg \square \bot$, the assertion that the system is consistent. In other words, if the system is consistent, then a liar sentence exists, so we have Gödel’s First Theorem, but now following in a modal context from Löb’s theorem rather than the diagonal lemma.

Exercise 2. Löb and fixed points. Show that the Fixed Point Theorem, applied to $A_2$ and $A_4$, are consistent with Löb’s theorem.

Conclusion

Although Gödel proved his First and Second Incompleteness Theorems using ingenious constructions in Peano arithmetic, they are complicated and obscure provability itself as a formal notion. Somewhat miraculously, a modal logic based on the Gödel-Löb’s axiom (equivalent to the Second Incompleteness Theorem) cleanly extracts the “provability fragment” of PA, a result known as Arithmetic Completeness. The Fixed Point Theorem is analogous to the diagonal lemma, giving us a recipe for constructing (simple logical equivalents of) fixed points. So we have a logical version of Gödel’s First Theorem!

For more details (and proofs of the two major results quoted here), Boolos’ book The Logic of Provability is your one-stop shop. Verbrugge’s article in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (SEP) is a little less daunting. For an introduction to Gödel’s theorems, Raatikainen’s SEP entry is a good place to start, and Raymond Smullyan’s monograph is a classic.

References

- The Logic of Provability (1993), George Boolos.

- Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems (2015), Panu Raatikainen. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems (1992), Raymond Smullyan.

- Provability Logic (2017), Rineke Verbrugge. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.