Extra

A unitary operator is an inner-product preserving change of basis, so the propagator just moves probability amplitude around the system.

Physically, at a finite temperature $T$, energies $E_n \gg k_\text{B} T$ are exponentially suppressed.

Since $\hat{H}$ is Hermitian, it follows that $U(t)$ is unitary:

\[U(t)^\dagger U(t) = e^{+i\hat{H}^\dagger t}e^{-i\hat{H}t} = e^{+i\hat{H} t}e^{-i\hat{H}t} = \mathbb{I}.\](For a stable system, we need a ground state, and we can always shift the energy so that this is positive. The requirement is not essential but makes things a bit simpler.)

Alternatively, using the rule for conditional probabilities,

\[\mathbb{P} (A | B) = \frac{\mathbb{P} (A \cap B)}{\mathbb{P} (B)},\]we can also view $P(B) \propto Z[\beta]$, and the normalisation as conditioning on the system being at fixed temperature $T$.

We can think of the terms $e^{-\beta E_n}$ as unnormalised probabilities for the system to have energy $E_n$, and $Z[\beta]$ as the normalisation factor.

Let’s return to our earlier, real-time expression $\mathcal{A}(\text{periodic in } t)$. Let ${|n\rangle}$ is the energy eigenbasis with energies ${E_n}$. Surprisingly, the amplitude for the system to be periodic in imaginary time $\tau = \beta$ is precisely the canonical partition $Z[\beta]$:

\[\mathcal{A}(\text{periodic in } -i\beta) = \mbox{Tr}\left[e^{-\hat{H}\beta}\right] = \sum_n \langle n|e^{-\hat{H}\beta}|n\rangle = \sum_n e^{-\beta E_n} = Z[\beta].\]This suggests that we view a thermal system as one which is periodic in imaginary time. It’s possible to check this works using the tools

We can make this analogy more precise, but this is the main formal trick and the key physical idea.

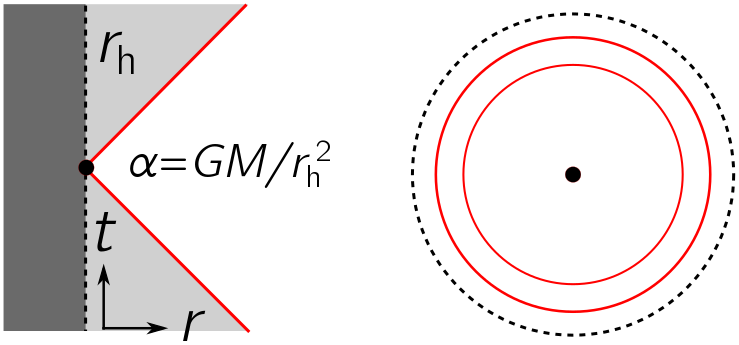

We also note that since $\alpha$ fixes the hyperbola, we can view $\xi$ as parameterising boosts to the observer.

There are in fact two strategies here:

- a direct argument based on the resemb

There is something peculiar about Rindler coordinates on the east wedge. Since an accelerating observer never leaves the wedge, they can never receive any signals from the west or north wedge. Effectively, there is a horizon, just like the event horizon of a black hole.

We will focus on simple black holes, with no charge or spin, for simplicity.

Fixing $\xi$, we get the straight line

\[\frac{t}{x} = \tanh\xi.\]Fixing $\alpha$, we obtain

\[ds^2 = -\frac{1}{\alpha^2}[\cosh^2\xi - \sinh^2\xi]\, d\xi^2 = -\frac{1}{\alpha^2}d\xi^2,\]so $\xi/\alpha$ is the proper time of an observer moving on the hyperbola labelled by $\alpha$.

Keeping $\alpha$ fixed, we can obtain the proper acceleration from the second derivative with respect to proper time:

\[\frac{\partial^2}{\partial (\xi/\alpha)^2} x^\mu = \alpha^2 x^\mu = \alpha (\sinh \xi, \cosh\xi),\]which has length $\alpha$. Thus, $\alpha$ is the magnitude of proper acceleration along the hyperbola.

both in $t$ and $\xi$:

\[t = -i\tau,\quad \xi = -i \theta.\]The change of coordinates is now

\[x = \alpha^{-1} \cos \theta, \quad \tau = \alpha^{-1} \sin\theta.\]In other words, $x$ and $\tau$ parameterise the position on a circle with period $2\pi\alpha^{-1}$ in imaginary time. But recall our earlier mantra, that periodicity in imaginary time means the system is thermal? That’s exactly what we have here! Define

If we restore the factor of $\hbar$ omitted from Schrödinger’s equation, and the factor of $c$ omitted from the Minkowski metric, we get the formula

\[T_\text{U} = \frac{\hbar \alpha}{2\pi k_\text{B} c}.\]Consider a quantum system with Hilbert space $\mathcal{H}$ and a time-independent, Hermitian Hamiltonian $\hat{H}$. Schrödinger’s equation states that $\hat{H}$ is the time evolution operator, which we can formally solve with an exponential:

\[i\partial_t |\psi(t)\rangle = \hat{H}|\psi(t)\rangle \quad \Longrightarrow \quad |\psi(t)\rangle = e^{-i\hat{H}t}|\psi(0)\rangle.\]This exponential is the propagator $U(t) = e^{-i\hat{H}t}$, and I can use it to evolve any state forward in time. Recall that the transition amplitude to go from an initial state $|\psi\rangle$ to a final state $|\phi\rangle$ in time $t$ is obtained by evolving $|\psi\rangle$ forward in time, then taking the overlap with the bra $\langle \phi|$:

\[\mathcal{A}(\phi, \psi; t) = \langle \phi| U(t)|\psi\rangle.\]If $|\psi\rangle = |\phi\rangle$, we have the probability the system returns to the state it started in in time $t$. For an orthonormal basis ${|n\rangle}$ of $\mathcal{H}$, the amplitude for the system to be periodic in time $t$ is just the sum over ${|n\rangle}$:

\[\mathcal{A}(t) = \sum_n \langle n| U(t)|n\rangle.\]So far, our discussion has assumed that $t$ is real. But what happens if we plug $t = -i\tau$ into the propagator? Formally making time imaginary is called a Wick rotation. Instead of evolving unitarily, it will squash things exponentially:

\[U(-i\tau) = U_E(\tau) = e^{-\hat{H}\tau}.\]If we expand in eigenvectors of $\hat{H}$, we see that when we evolve in imaginary time $\tau$, things get suppressed according to their energy. But this should remind us of thermal systems! Indeed, recall that for a system with energies ${E_n}$, the canonical partition function at temperature $T = 1/\beta$ is

\[Z[\beta] = \sum_n e^{-\beta E_n}.\]This is precisely the “amplitude” for the system to be periodic in imaginary time $\beta$:

\[\mathcal{A}(-i\beta) = \sum_n \langle n|e^{-\hat{H}\beta}|n\rangle = \sum_n e^{-\beta E_n} = Z[\beta].\]Since the partition function encodes the statistical properties of a thermal system, this suggests we should view thermal systems as those which are periodic in imaginary time. We could expend more effort justifying this, but the connection between propagators and partition functions is the main idea. So, although it sounds crazy, repeat after me: if a system is periodic in imaginary time $\beta$, we can regard it as thermal at temperature $T = 1/\beta$.

Any time we want to evaluate some observable $\hat{A}$, for instance some classical measuring device, the probability distribution over states leads to

\[\langle\hat{A}\rangle = \frac{1}{Z[\beta]}\sum_E e^{-\beta E}\langle\hat{A}\rangle_E = \frac{1}{Z[\beta]}\sum_E \mbox{Tr}[e^{-\beta \hat{H}}|E\rangle\langle E| \hat{A}] = \mbox{Tr}[\hat{\rho}_\beta\hat{A}].\]This has a simple interpretation. It

Roughly, space itself is the quantum system due to the existence of quantum fields, such as the photon, which can be excited at any location. This means that an accelerating observer will see a thermal bath of photons at the Unruh temperature. We can derive this result rigorously (see the references), but imaginary time gives us a nice shortcut!

Conical deficits and cigars*

In deriving both the Unruh and Hawking effect, I’ve made a subtle assumption about the Euclidean geometry: the absence of a conical deficit. A conical deficit occurs when the polar angle $\theta$ subtends less than $2\pi$, so that the geometry of a circle is wrapped up into a cone. We can easily see how this happens from a picture:

There is a simple way of seeing this doesn’t happen, for either Rindler coordinates or black holes,