November 4, 2020. The central dogma of flat earthism would seem to be that the earth is flat. More recently, though, heretics have appeared on the scene claiming the earth is shaped like a donut. In this post, I’ll explain how you can have your donut and eat it too: the earth could be both flat and torus-shaped, by embedding in higher dimensions! I’ll examine some amusing implications and (decisive) objections to this model.

Introduction

From 1519–1522, Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan circumnavigated the world around a rough circle of latitude. Led by Sir Ranulph Fiennes, in 1979–1982, the Transglobe Expedition completed the first longitudinal circumnavigation by ground transport (i.e. no planes). So, if we draw latitude and longitude on a rectangle (the Mercator projection), it seems the earth has periodic boundary conditions.

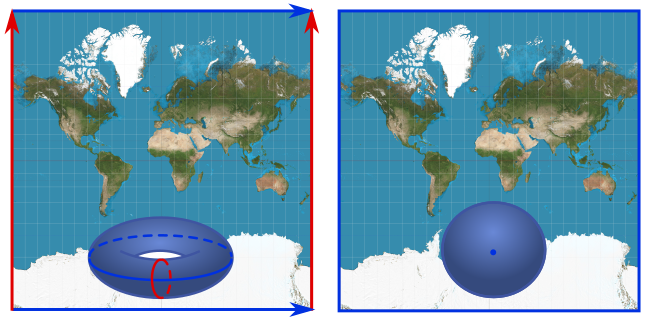

There are two possibilities consistent with these expeditions. First, the top and bottom are glued, and the left and right glued, but these gluings are separate. As illustrated below left, doing this gluing yields a donut. If, on the other hand, we explain the periodicity by gluing all four sides together, we get a surface with the topology of a sphere, shown below right. Thus, we are led naturally to consider the sphere and the donut as two options for the shape of the earth.

Moving beyond the rough shape of the earth, we come to the question of geometry, properties of lengths, angles, and curves on the earth’s surface. Prior to flatness, even, there is a simpler observation we can make: the earth looks more or less the same everywhere. If there were no mountains or valleys, you would be hard-pressed to tell where you are by drawing large triangles on the ground. So the question now becomes: given our two topological possibilities of donut and sphere, can we equip them with geometries which look the same everywhere?

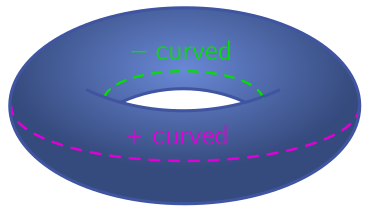

For our second option—a closed surface with no holes—the only possibility is a uniform sphere. This is what our earth in fact looks like, apart from a little squashing at the poles. So this is constent with the boundary conditions and uniformity. What about the donut? The standard way of embedding a donut, or torus in the mathematical language, looks very different as you move around. On the outside, it is positively curved, bulging outwards like a sphere, but on the inside, it is negatively curved like a saddle. We will define curvature below, but the point is that you could detect this different by carefully drawing large triangles. Does this rule the torus out as a possible shape for the earth?

Not quite! There a sneaky math factoid we can use: you can embed a torus in four spatial dimensions in such a way that it is not only constant curvature, but flat. This naturally combines both flat earthism and donut earthism! I’ll demonstrate how the construction works in an elementary way below. An obvious objection is that we only see three dimensions, not four, so I will talk about a physicist’s trick for localizing physics called a “braneworld”. This has the other benefit of explaining why gravity is weak. I’ll end with some more serious objections which, to my mind, decisively rule out the possibility we live in a flat, toroidal braneworld.

Theorema Egregium and the flat torus

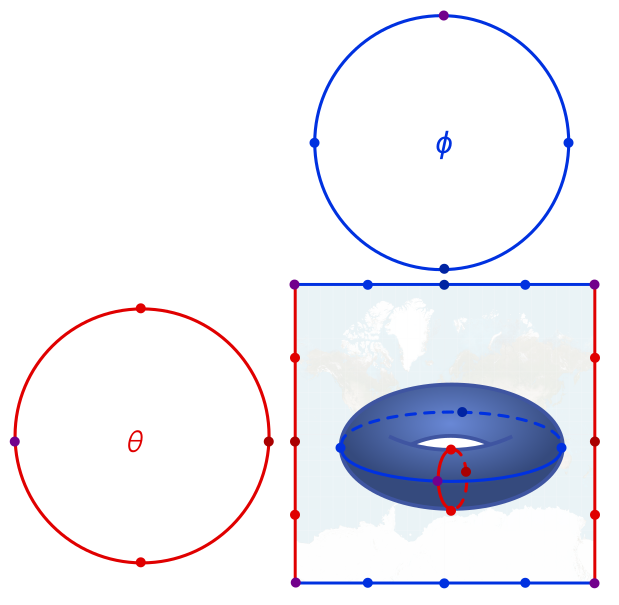

Let’s start by constructing the flat torus. Recall that the donut has a blue edge of latitude which is glued at the ends, and a red edge of longitude which is glued at the ends. If we do this in three dimensions, we get a torus which curves differently on the inside and the outside. But suppose that each coloured edge has a separate two-dimensional plane where it gets rolled into a circle. We picture this below, as well as a “curved” torus to help us visualise things.

Since each circle needs two dimensions, there are four dimensions altogether. But the torus itself is still a two-dimensional surface! We can label it with a latitude coordinate $\phi \in [0, 2\pi)$ and a longitude coordinate $\theta \in (-\pi, \pi]$. We no longer have north and south poles, but rather, north and south “circles” at $\theta = \pi/2$ and $\theta = -\pi/2$. The equator