February 19, 2021. A self-contained derivation of the most famous equation in physics. I start with a crash course on special relativity, emphasizing the invariance of spacetime lengths, move on to conservation laws, and end by considering the relativistic mechanics of an exploding bowling ball.

Contents

- Introduction

- Spacetime trigonometry

- Time dilation

- Factorising spacetime

- Velocity addition

- Conservation laws

- Mass effect

- The most famous equation

- Exercises

1. Introduction

I recently stumbled across the book “Why does $E = mc^2$?” by Brian Cox and Jeff Forshaw in a used bookstore. I realized, to my chagrin, that I didn’t know the answer! As a theoretical physicist, this was somewhat embarrassing. So, rather than buy the book, I decided I would make it my homework not only to derive it from what I knew about special relativity, but to try and write up my reasoning in a self-contained way. This post is my homework.

A few preliminary comments. First, the exercise section is optional, mostly designed to fill in details and connect to standard treatments of the subject. Second, unlike Einstein, I have not made any references to the energy of light. This leads to an argument which is longer but more conceptually minimal. Finally, these notes gave me the opportunity to dust off some old ideas about how to present special relativity, guiding in particular my choice to do everything in one spatial dimension. I hope my mildly eccentric approach can be of benefit to others.

2. Spacetime trigonometry

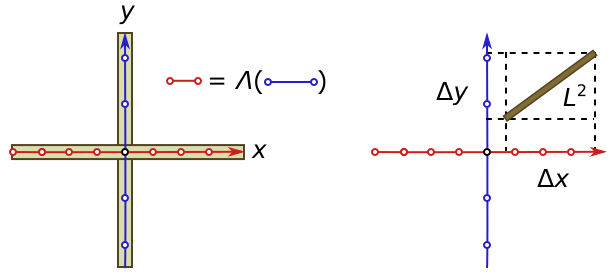

Relativity is really just the bizarro version of trigonometry. To make this obvious, we’ll present Pythagoras’ theorem in an odd way. Suppose we have rulers, $x$ and $y$, oriented at right angles [1], and which both have evenly spaced marks. An $x$-division need not equal a $y$-division, and in general will correspond to $\Lambda$ units of $y$. We can measure lengths, say of a plank of wood, in this system, by simply recording the number of marks it takes up on ruler $x$, call it $\Delta x$, and the number of marks taken up on $y$, called $\Delta y$. Pythagoras’ theorem means that, however we choose to orient the plank of wood or the rulers themselves, we always find

\[d^2(\Delta x, \Delta y) = \Delta x^2 + \Lambda^2 \Delta y^2 = L^2,\]for some fixed number $L$, depending only on the piece of wood we’ve chosen to measure. It seems reasonable to define $L$ as its length. But even more importantly, the quantity $d^2$ is invariant under a change in relative orientation. We describe relative orientation more explicitly in Exercise 1.

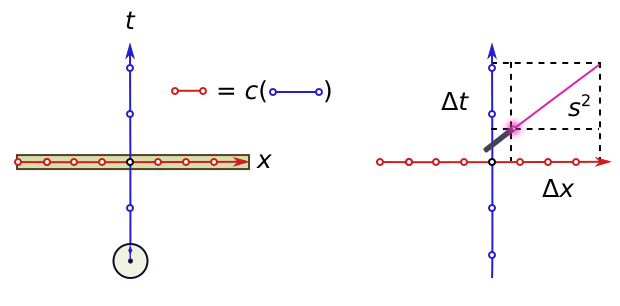

Relativity parallels this setup closely. Michelson and Morley’s famous experiment in 1887 suggested that the speed of light does not depend on how fast you are going when you measure it. Einstein arrived at the same conclusion by thinking long and hard about electrodynamics. To measure the speed of light, we use two rulers, $x$ and $t$, though the latter is usually called a “clock”.

The light travels between two points a distance $\Delta x$ apart in time $\Delta t$, so the speed is $c = \Delta x/\Delta t$. We can rewrite this suggestively as

\[s^2(\Delta x, \Delta t) = \Delta x^2 - c^2 \Delta t^2 = 0.\]The analogy is hopefully clear. The ratio between units of $x$ and units of $t$ is given by $c$. The expression $s^2(\Delta x, \Delta t)$ defines a “spacetime length”, obeying a spacetime version of Pythagoras’ theorem, namely that the $s^2$ distance between events does not change even when we speed up or slow down. More precisely,

\[s^2(\Delta x, \Delta t) = \Delta x^2 - c^2 \Delta t^2 = \text{constant}, \tag{1} \label{s2}\]when $\Delta x$ and $\Delta t$ are the space and time separation of any two events, as measured by an observer at constant speed. As a special case, $s^2 = 0$ for a light ray travelling from $A$ to $B$, whatever speed we are moving. Hence, light always travels with velocity $c$. But the implications of (\ref{s2}) are much broader! See Exercise 4 for a discussion of what happens if we only ask for invariance of $s^2 = 0$.

3. Time dilation

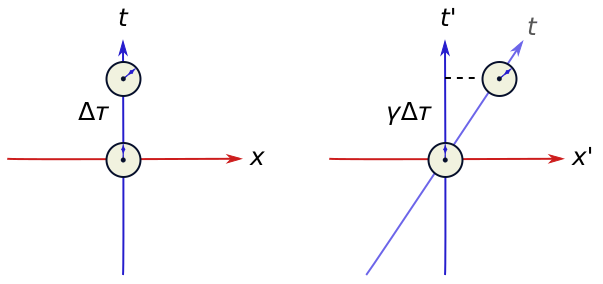

We can use (\ref{s2}) to quickly deduce that time dilates and length contracts. Consider a clock which ticks out time $\tau$ in its own frame of reference, i.e. where it is stationary. We call this the proper time. For a proper time interval $\Delta \tau$, the clock moves nowhere ($\Delta x= 0$), so the spacetime length is

\[s^2(0, \Delta \tau) = -c^2 \Delta \tau^2.\]If the clock moves at speed $v$ in our reference frame, then in time $\Delta t$ (as measured by our clock), it moves a distance $\Delta x = v \Delta t$. Thus, the spacetime length is

\[s^2(\Delta x, \Delta t) = \Delta x^2 - c^2 \Delta t^2 = \left(\frac{\Delta x^2}{c^2\Delta t^2} - 1\right) c^2\Delta t^2 = -c^2\Delta t^2\left(1 - \frac{v^2}{c^2}\right).\]But since the spacetime length is invariant, we have

\[-c^2 \Delta \tau^2 = -c^2\Delta t^2\left(1 - \frac{v^2}{c^2}\right) \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \frac{\Delta t}{\Delta \tau} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-(v/c)^2}} = \gamma, \tag{2} \label{gamma}\]where we have defined the all-important Lorentz factor $\gamma$. Note that $\gamma \geq 1$, so that less proper time ($\Delta \tau$) passes for the clock than elapsed time ($\Delta t$) measured in our reference frame. Thus, the moving clock appears to slow down, a phenomenon called time dilation. In Exercise 2, we work out an implication for moving rulers called length contraction.

Note that from (\ref{gamma}), a moving clock appears to stop at $v = c$. Put differently, no time passes for a light ray!

4. Factorising spacetime

There is a cute way to understand how measurements change when we speed up or slow down. Since the spacetime length is a difference of squares, we can factorise it:

\[s^2(\Delta x, \Delta t) = \Delta x^2 - c^2 \Delta t^2 = (\Delta x + c \Delta t) (\Delta x - c \Delta t) = \Delta x^+ \Delta x^-,\]where $x^\pm$ represents the “combined rulers” $x \pm ct$. Then $s^2$ will be invariant under changes of velocity provided that, in a new frame of reference with rulers $x’, t’$, we have

\[(\Delta x')^+ = \alpha \Delta x^+, \quad (\Delta x')^- = \frac{1}{\alpha}\Delta x^-, \tag{3} \label{boost}\]for some factor $\alpha$. To connect $\alpha$ to the relative velocity, we consider the moving clock experiment. Remember that in the clock frame $\Delta x = 0$ and $\Delta t = \Delta \tau$, but in our frame, $\Delta t’ = \gamma \Delta \tau$ and $\Delta x’ = v \Delta t’ = v\gamma \Delta \tau$. Thus, we have

\[\alpha^{2} = \frac{(\Delta x')^+}{(\Delta x')^-} \cdot \frac{\Delta x^-}{\Delta x^+} = \frac{(v + c)\gamma \Delta \tau}{(v - c)\gamma \Delta \tau} \cdot \frac{ -c\Delta\tau}{+c\Delta\tau} = \frac{c+v}{c-v}. \tag{4} \label{alpha}\]From this equation, we can deduce the rule for transforming quantities between different frames, the Lorentz transformation. The details are worked out in Exercise 3. In Exercise 4, we also determine the more general class of transformations which leave the speed of light fixed, but allow $s^2$ to vary for nonzero values.

5. Velocity addition

We can use equation (\ref{alpha}) to chain together multiple changes of frame. For instance, suppose a rocket moving at speed $v$ in our frame ($x’’, t’’$) launches a clock at speed $u$ in its frame ($x’, t’$). The speed of the clock in our frame is $u’’ = \Delta x’’/\Delta t’’$, and obeys

\[\frac{(\Delta x'')^+}{(\Delta x'')^-} = \frac{\Delta x'' + c\Delta t''}{\Delta x'' - c\Delta t''} = \frac{u'' + c}{u'' - c}.\]But we can also just use (\ref{alpha}) twice:

\[\begin{align*} \frac{(\Delta x'')^+}{(\Delta x'')^-} & = \left(\frac{c+v}{c-v}\right) \frac{(\Delta x')^+}{(\Delta x')^-} \\ & = \left(\frac{c+v}{c-v}\right) \left(\frac{c+u}{c-u}\right) \frac{\Delta x^+}{\Delta x^-} \\ & = - \left(\frac{c+v}{c-v}\right) \left(\frac{c+u}{c-u}\right). \end{align*}\]Combining the last two equations, we find

\[\frac{u'' + c}{u'' - c} = \left(\frac{c+v}{c-v}\right) \left(\frac{c+u}{c-u}\right) \quad \Longrightarrow \quad u'' = \frac{v + u}{1+ uv/c^2}, \tag{5} \label{add}\]after some algebra to isolate $u’’$. This is the famous velocity addition formula! I’ll let you check the algebra in Exercise 5.

6. Conservation laws

So far, we haven’t really done any physics, just bizarro trigonometry. Let’s rectify that and introduce some ideas from Newtonian mechanics. Suppose we have a bowling ball of mass $m$ and speed $v$. Two ways to quantify its motion are momentum $p$, and the kinetic energy $K$:

\[p = mv, \quad K = \frac{1}{2}mv^2.\]A consequence of Newton’s laws [2] is that if the force on a bowling ball is zero, its momentum doesn’t change. In fact, if the total force on a collection of bowling balls is zero, the total momentum cannot change, even if they collide! We say that momentum is conserved. So if one bowling ball ($m_1, v_1$) collides with another ($m_2, v_2$), the combined momentum is the same before and afterwards:

\[P = p_1 + p_2 = m_1 v_1 + m_2 v_2.\]A sneakier conserved quantity is mass. We usually assume $m_1$ and $m_2$ remain fixed, but if the bowling balls shatter into parts, not only is the total $P$ conserved, but also the sum of masses of the fragments. In contrast, kinetic energy need not be conserved, since energy can change forms, e.g. from kinetic to energy of deformation when the bowling balls shatter. We’ll return to conservation of energy below.

Let’s continue to assume that momentum and mass are conserved in any frame of reference in special relativity, and see what that implies. To make things concrete, we’ll use the example of an exploding bowling ball. Let’s start in the rest frame of the bowling ball, where the mass is $2M_0$ (as measured by stationary scales), and the momentum $P_i = 0$, since the velocity is zero by definition. At some point, an explosive device inside the bowling ball detonates, splitting it into two equal halves of mass $M_0$. To ensure momentum is conserved, these zoom off with equal and opposite velocities $\pm u$, so

\[P_f = M_0u + M_0(-u) = 0 = P_i.\]Let’s now go to the frame of the part moving left at speed $u$. Before the explosion, the bowling ball (in this frame of reference) was moving at speed $u$ to the right, so the momentum was presumably

\[P'_i = 2M_0u.\]After the collision, one half is stationary (we have chosen to go to its rest frame), and the other moves at a speed given by the velocity addition formula (\ref{add}):

\[u' = \frac{2u}{1 + u^2/c^2}. \tag{7} \label{double}\]If the second half has mass $M_0$, the momentum after the collision is

\[P'_f = \frac{2M_0u}{1 + (u/c)^2}.\]This is clearly different from the initial momentum $P’_i$ for nonzero $u$! It looks, naively, as if conservation of mass and momentum are not consistent with relativity after all. You can check in Exercise 6 that this problem persists in other reference frames.

7. Mass effect

But this is a little too quick. Mass may be conserved in a frame, but it need not be invariant between frames. And we can get $P’_f$ to equal $P_i’$ by increasing the final mass. Inspired by our results for time dilation and length contraction, we guess that the rest mass $m_0$ (measured in the frame it is stationary) increases as $m = \gamma m_0$ in a moving frame. We can check this guess is sensible. First, note that in the stationary frame of the unexploded bowling ball, the exploded halves have a rest mass less than $M_0$:

\[m_0 = \frac{M_0}{\gamma} = M_0\sqrt{1-\left(\frac{u}{c}\right)^2}. \tag{8} \label{rest}\]In the moving frame, the original bowling ball moves at speed $u$, so its mass is

\[2M = 2M_0 \gamma,\]and hence its momentum is

\[P'_i = 2M u = 2M_0 \cdot \frac{u}{\sqrt{1+(u/c)^2}}.\]After the collision, one half is stationary, while the other half moves away at speed $u’$ given by (\ref{double}). The associated Lorentz factor is

\[\begin{align*} \gamma' = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - (u'/c)^2}} & = \left[1 - \frac{4u^2}{c^2(1 + (u/c)^2)^2}\right]^{-1/2} \\ & = \frac{c(1 + (u/c)^2)}{\sqrt{c^2(1 + (u/c)^2)^2 - 4u^2}} \\ & = \frac{1 + (u/c)^2}{\sqrt{(1 - (u/c)^2)^2}} = \frac{1 + (u/c)^2}{1 - (u/c)^2}. \end{align*}\]The momentum for this second half is therefore

\[\begin{align*} P'_f = 2 m_0 \gamma' u' & = 2 M_0 \cdot \frac{\gamma' u'}{\gamma} \\ & = 2M_0 \cdot \frac{1 + (u/c)^2}{1 - (u/c)^2} \cdot \frac{2u\sqrt{1-(u/c)^2}}{1 + u^2/c^2} \\ & = 2M_0 \cdot \frac{u}{\sqrt{1+(u/c)^2}} = P'_i. \end{align*}\]With this rule, momentum is indeed conserved! We give a more general argument that $m = \gamma m_0$ and $p = mv$ are conserved in Exercise 7.

8. The most famous equation

We’ve motivated the transformation law $m = \gamma m_0$, but we have yet to explain why $E = mc^2$. To see why, let’s return to the exploding bowling ball in its rest frame. Recall from equation (\ref{rest}) that the rest mass of the halves is actually slightly smaller than $M_0$. To see what’s going on, let’s consider the low-speed limit $u \ll c$. Using the binomial approximation, we have

\[\left[1 - \left(\frac{u}{c}\right)^2\right]^{-1/2} \approx 1 + \frac{u^2}{2c^2}.\]Applying this to (\ref{rest}) gives

\[M_0 = m_0 \left[1 - \left(\frac{u}{c}\right)^2\right]^{-1/2} \approx m_0 + \frac{1}{2c^2}m_0 u^2.\]Remember that $M_0$ is fixed. As $u$ increases, the second term on the RHS gets bigger, so the rest mass $m_0$ must get smaller. That’s kind of weird! It’s almost as if the mass is being converted into something else. If we multiply this equation through by $c^2$, it becomes clearer what this “something else” is:

\[M_0c^2 \approx m_0c^2 + \frac{1}{2}m_0 u^2. \tag{9} \label{energy}\]The last term is just the classical kinetic energy of the fragment! So mass seems to be converted into kinetic energy. The maximum amount that can be converted into kinetic energy is $M_0c^2$, and the leftover energy is $m_0 c^2$. This suggests that the total energy of the body is $M_0c^2$. Writing the relativistic mass as $m$ instead of $M_0$, we have the most famous equation of all time:

\[E = mc^2. \tag{10} \label{emcc1}\]This relation even tells us something about massless particles, as we explore in Exercise 8. You might wonder why $E = mc^2$ should be interpreted as the total energy, rather than some special form of mass energy. The answer is simply that, if we interpret it this way, the mysterious “conservation of mass” we have been dragging around becomes conservation of total energy! And unlike kinetic energy, which can get converted into other things, one of the fundamental principles of physics is that total energy is conserved. This also tells why we continue to interpret $mc^2$ as total energy even at high speeds, where we cannot interpret mass-energy as getting converted into classical kinetic energy (since the binomial approximation breaks down). So everything hangs together nicely! Hopefully you now have a sense of why Einstein’s famous formula is true.

9. Exercises

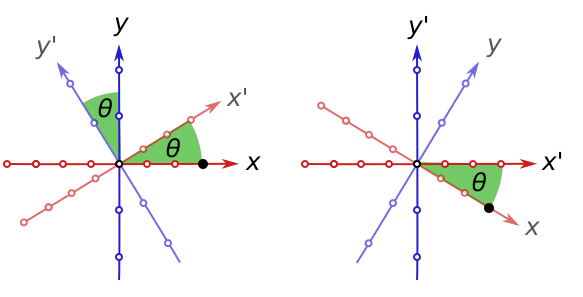

Exercise 1 (rotations). To make the analogy to spacetime more convincing, in this exercise we’ll describe relative rotations more explicitly. Let’s take our original perpendicular rulers $x, y$ and rotate them anticlockwise by some angle $\theta$ into new rulers $x’, y’$, keeping the origin fixed for the moment. Mark a point a distance $d$ along the $x$ axis.

In the $x’, y’$ system, we define functions $\cos(\theta)$ and $\sin(\theta)$ by

\[x' = d\cos (\theta) = x\cos (\theta), \quad \Lambda y' = -d\sin (\theta) = x\sin (\theta),\]where $x$ denotes the $x$-coordinate of the point.

(a) Argue that a point on the $y$ ruler, $d$ marks along, goes to coordinates

\[x' = d\Lambda \sin(\theta) = -y\Lambda \sin(\theta), \quad y' = d\cos(\theta) = y\cos(\theta).\](b) Use the equations above to show that, if we move the $x, y$ system around and then rotate by $\theta$, the displacements $\Delta x$ and $\Delta y$ become

\[\begin{align*} \Delta x' & = \cos(\theta) \Delta x + \sin(\theta) \Lambda \Delta y \\ \Lambda\Delta y' & = -\sin(\theta) \Delta x + \cos(\theta) \Lambda \Delta y. \end{align*}\](c) Check that

\[d^2(\Delta x', \Delta y') = d^2(\Delta x, \Delta y) [\cos^2(\theta) + \sin^2(\theta)].\]Pythagoras’ theorem is then equivalent to the trigonometric identity

\[\cos^2(\theta) + \sin^2(\theta) = 1.\](d) Consider any point on the $y$ ruler, and define $q =\Delta x’/\Delta y’$. Verify that

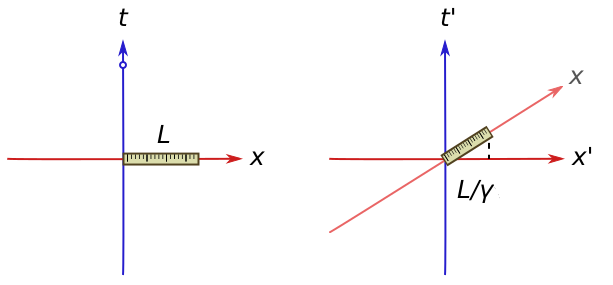

\[\tan(\theta) = \frac{\sin(\theta)}{\cos(\theta)} = \frac{q}{\Lambda}.\]Exercise 2 (length contraction). Time dilation can be used to deduce a rule for length in different frames.

(a) Suppose a ruler passes us by at speed $v$. We can deduce its apparent length $L’$ by timing how long it takes ($\Delta \tau$) to pass some specific spot. Show this length is

\[L' = v\Delta \tau\]where $\Delta \tau$ refers to the clock which is stationary in our frame.

(b) The proper length $L$ of the ruler is the length measured in the frame where it is stationary. It can read this off by looking at our clock. Using time dilation, show that

\[L = \gamma L'.\]

Thus, a moving ruler shrinks by a factor $\gamma$ in our frame. This is called length contraction.

Exercise 3 (Lorentz transformations). In this exercise, we will derive something called the Lorentz transformation. First, we define $\alpha = e^\eta$ for a “boost parameter” $\eta$. We will also use the hyperbolic functions

\[\cosh(\eta) = \frac{1}{2}(e^\eta + e^{-\eta}), \quad \sinh(\eta) = \frac{1}{2}(e^\eta - e^{-\eta}), \quad \tanh(\eta) = \frac{\sinh(\eta)}{\cosh(\eta)}.\]These play the same role in relativity that the trigonometric functions $\sin, \cos, \tan$ play in Euclidean geometry, namely, parameterising transformations which keep length invariant.

(a) Suppose two events are separated by $\Delta x, \Delta t$ in the $x, t$ frame. Using (\ref{boost}), show that in the $x’, t’$ frame, they are separated by

\[\begin{align*} \Delta x' & = \cosh(\eta) \Delta x + \sinh(\eta) c \Delta t \\ c\Delta t' & = \sinh(\eta) \Delta x + \cosh(\eta) c \Delta t. \end{align*}\]This is very clearly analogous to the results in Exercise 1!

(b) From the clock example (or otherwise), argue that

\[\cosh(\eta) = \gamma, \quad \sinh(\eta) = \frac{\gamma v}{c}.\]Inserting these into (a) gives the standard form of the Lorentz transformation:

\[\Delta x' = \gamma \Delta x + \gamma v \Delta t , \quad \Delta t' = \left(\frac{\gamma v}{c^2}\right)\Delta x + \gamma\Delta t. \tag{6} \label{lorentz}\](c) Show that (b) is consistent with the results of (\ref{alpha}), i.e. both imply $\tanh(\eta) = v/c$. Explain why this is analogous to part (d) of Exercise 1.

Exercise 4 (null hypothesis). We’ve assumed that (\ref{s2}) is invariant in general, but light obeys $s^2 = 0$. What if we only require invariance for this special case? Using our new coordinates $x^\pm$, we can investigate!

(a) Argue that $s^2 = 0$ is invariant if and only if

\[(\Delta x')^\pm = \alpha_\pm \Delta x^+\]for constants $\alpha_\pm$. As above, we’ll take these to be positive for simplicity.

(b) Show that for some $\alpha, \lambda > 0$, we can always rewrite

\[\alpha^+ = \alpha \lambda, \quad \alpha^- = \frac{\lambda}{\alpha}\](c) Argue that the most general transformation preserving $s^2 = 0$ is a Lorentz transformation followed by a uniform scaling:

\[x' = \lambda x, \quad t' = \lambda t.\](d) Finally, conclude that if we restrict to transformations induced by relative motion between frames, invariance of the speed of light implies invariance of $s^2$ for any value. Hint. What is the relative velocity for a pure scaling, i.e. $\alpha = 1$?

Exercise 5 (additional algebra). Do the algebra to make $u’’$ the subject in (\ref{add}).

Exercise 6 (new frame). Consider a frame of reference in which the unexploded bowling ball moves right at speed $v$, e.g. while bowling.

(a) Show that the two exploded halves move with velocities

\[u'_\pm = \frac{v \pm u}{1 \pm uv/c^2}.\](b) If each has mass $M_0$, show that momentum is only conserved for $u = 0$ or $v = c$.

Exercise 7 (conserving two-momentum). Suppose a particle of rest mass $m_0$ moves at speed $v$ for proper time $\Delta \tau$. The two-velocity $\mathbf{v}$ and two-momentum $\mathbf{p}$ are vectors [3]

\[\mathbf{v} = \frac{1}{\Delta \tau}(\Delta t, \Delta x) , \quad \mathbf{p} = m_0\mathbf{v}.\](a) Show that two-quantities can be written

\[\mathbf{v} = (\gamma, \gamma v), \quad \mathbf{p} = (\gamma m_0, \gamma m_0 v).\](b) Suppose that the two-momenta before and after a collision are equal:

\[\mathbf{p}_i = \mathbf{p}_f.\]Argue that, after a Lorentz transformation (\ref{lorentz}) to a new frame of reference $x’, t’$, the two-momentum remains conserved:

\[\mathbf{p}'_i = \mathbf{p}'_f.\]This means that if relativistic mass $\gamma m_0$ and momentum $\gamma m_0 v$ are conserved in one frame, they are conserved in any other!

(c) At low speeds ($v \ll c$), the Lorentz factor $\gamma \approx 1$. We also know that at low speeds, Newtonian mechanics is a good description, so mass $m_0$ and momentum $m_0v$ are conserved. Extrapolate to the conservation of two-momentum.

Exercise 8 (energy-momentum). We end with an equivalent form of Einstein’s equation

(a) First, show that

\[c^2\gamma^2 = \gamma^2 v^2 + c^2.\](b) Deduce the energy-momentum relation

\[E^2 = p^2 c^2 + m_0^2 c^4.\](c) A photon has zero rest mass. Use the energy-momentum relation to argue that the energy and momentum are related by

\[E = pc.\]Maxwell deduced this from classical electromagnetism, but amusingly, we got there by think about bowling balls!

Or if you prefer, an orthogonal grid of such rulers.

Newton's second law can be written $F = \Delta p/\Delta t$, i.e. the force is just the rate of change of momentum. When force is zero, so is the momentum change!

The "two" refers to the total number of spacetime dimensions. For three dimensions of space and one of time, the corresponding quantities are called four-velocity and four-momentum.